A Naive Generative Model

11/21/16

Rather than dive immediately into complex neural network architectures, I wanted to create a first model that predicts the absolute pitches of one voice given the absolute pitches in other voices. My goal was not to create the best possible predictive model of music so much as it was to create a control against future experiments that pre-process the training data further. If the dataset I had found could be modeled with high accuracy without significant pre-processing, then any more sophisticated model would be unnecessary and I would know to find a less homogeneous dataset before proceeding.

Music Data

But first, let’s talk about music datasets. My starting point was 382 chorales by J.S. Bach encoded as midi files (compiled by Nicolas Boulanger-Lewandowski). I like working with Bach in machine learning for a number of reasons. First, Bach’s music was extremely regular – he adhered to an absurd number of restrictions while writing that stayed relatively consistent throughout his life, so his music makes for fairly homogeneous datasets. Second, Bach was incredibly prolific – he wrote hundreds of cantatas, chorales and polyphonic works for keyboard instruments, which means we can assemble large datasets. Third, Bach’s style is very well known, but not many of his works are, so music that imitates Bach is more likely to fool the average listener than music imitating another composer.

In the future, I’d also like to experiment on larger, more varied musical datasets, however most of the organized data in machine learning dataset collections online is either raw audio data or a link to a website that indexes many individual files. Despite this lack of easy data, I’m looking into two further midi datasets (which I’ll probably talk about in a future post), midi transcriptions of national anthems (which are similarly a well-known style, but not well-known individually) and midi transcriptions of string quartets by various composers (much less homogeneous, but still polyphonic and in four voices). More on that later.

Encoding Schemes

Music notation traditionally hasn’t been the easiest thing for computers to work with. Since score notation dates back to Guido of Arezzo in the 11th century (who didn’t have machine encoding as a priority) and was designed to express contour of a melody to singers rather than encode specifically what a piece should sound like at a given time. Further, since musical events can happen continuously through time, it’s difficult to split music into discrete timesteps, which is necessary if we want to apply machine learning techniques.

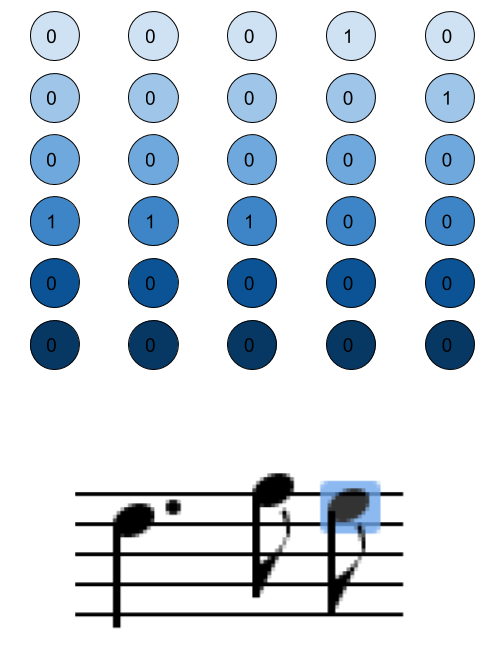

Midi solves some of these problems – midi events are either “note on” or “note off” signals and are encoded with their distance from the previous timestep in the channel, so we can easily figure out what notes are being played at any given point in time. Since recurrent neural nets have issues with long-term dependencies, so I don’t want to use the 480 timesteps per quarter note that is standard in midi when my shortest notes are much longer than (and divisible by) the length of a timestep. Instead, I make a single timestep in my encoding the GCD of my note lengths. Notes are then put in one-hot encoding timestep by timestep based on pitch with a total encoding size from the minimum midi note value to the maximum.

RNNs and LSTM Layers

Rather than write yet another blog post on the internet explaining how recurrent neural networks and their common implementation, long short term memory (LSTM) layers, I’ll leave that to far better writers who understand the technical details better than I do.

The conceptual takeaway as far as this project is concerned is that these neural network layers have internal state that allows the output for a timestep to depend on prior timesteps and for the rules for those dependencies (when to “remember”, when to “forget”) to be learned using backpropagation just like the weights of a feedforward network.

The last remaining issue is that neural networks output continuous values while our music encoding is entirely discrete. As is common practice with nominal classification problems, we interpret the output of the network as a multinomial probability distribution. When generating, we sample from that distribution immediately to get the network’s prediction for the next timestep, then feed the result back into the network. When training, however, we don’t want to train the network on the wrong conditional probabilities (i.e. if we want it to predict a piece that starts with an ‘A’ followed by a ‘C’, and it guesses ‘F#’ for the first note, we shouldn’t train it to output ‘C’ after an ‘F#’), so we instead don’t sample and assume that, no matter what the probabilities were, that the network guessed correctly.

Simple Generative Model

Now that all of the background is out of the way, we can talk about this first model. As an input to the network, I feed a one-hot encoded vector of notes from all voices at the previous timestep, and all but one voice at the current timestep into a recurrent neural network with three LSTM hidden layers, take the output, put it through a softmax function, and train the network to output a prediction of the missing voice.

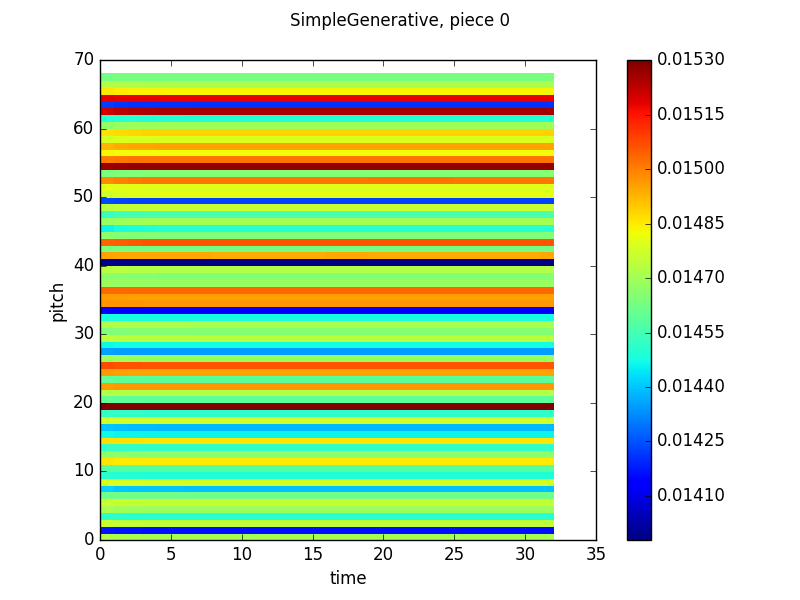

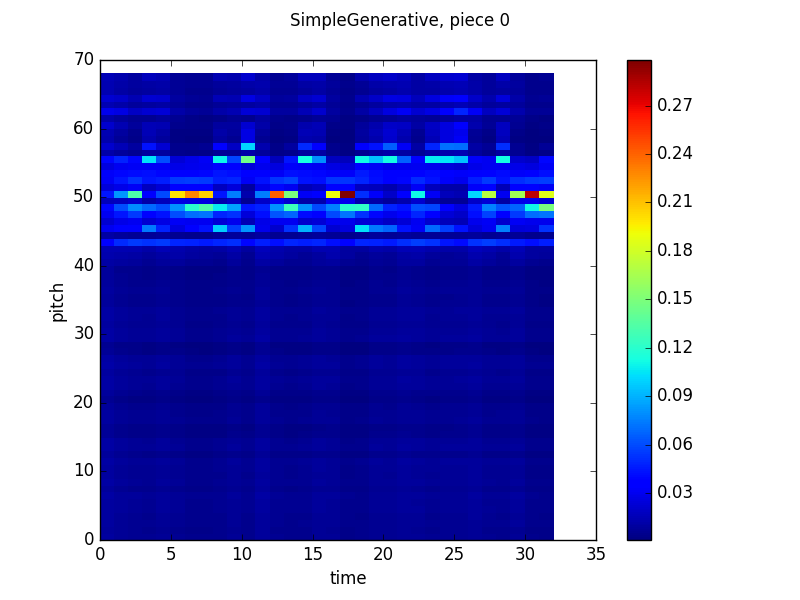

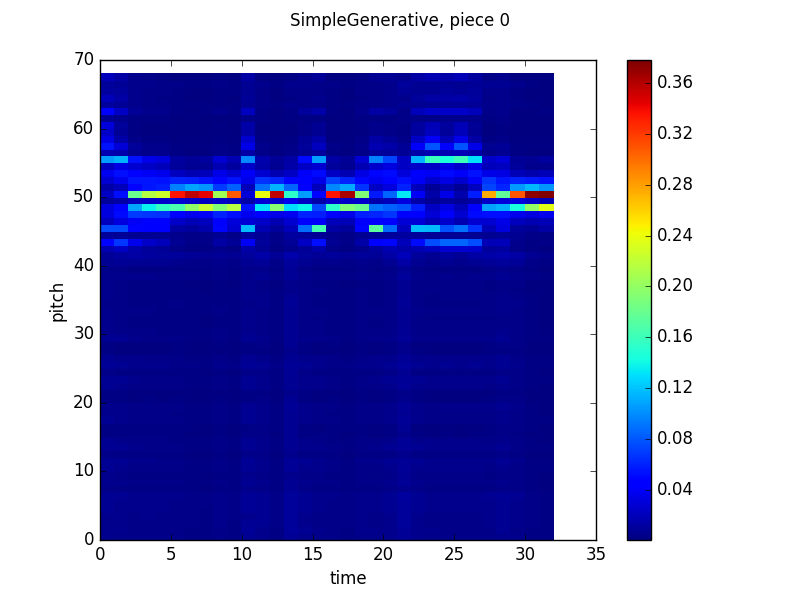

Here are some pretty pictures of the training process:

Here, the Y-axis is pitch, the X-axis is time and the heatmap color at timestep n and pitch m is the probability that the network will output that pitch given the previous n-1 timesteps of the actual piece. These are pulled from validation runs, so there aren’t corresponding examples of generated music.

As you can see, the model does try to fit, but ultimately fails. The network tends to just output high probabilities for more common pitches at every timestep rather than identify conditional relationships between timesteps. My guess to why is that absolute pitches that correlate together in one piece do not correlate together in another piece, mostly as a result of key relationships and tonality (eg. a C following an E in C major is likely and makes sense while a C following an E in D major is unlikely (at least in Bach chorales), since it is a flat leading tone). One of my goals is for the neural network to learn relationships between notes without any assumptions about a tonic or tonality in general, so the easy answer of transposing all of the pieces to the same key would remove that side of the learning.

What Comes Next?

Well, I’m writing these posts retroactively, so I’m currently several steps ahead of my writing (I finished this model around the first week of October). In another post, coming out shortly, I’ll detail my forays into some other “expert” models that measure different attributes of the training data (voice spacing, voice contour and metric position), then talk about what happens when you multiply the outputs of those models together.