Taking the Product

1/1/17

After finishing the individual expert models, I moved on to building a product model. The concept comes from Geoffrey Hinton and this particular application was my colleague from summer research, Daniel Johnson’s idea. Basically, instead of training naively on untransposed pitches, preprocess that pitch data in a variety of different ways, then train several “expert” models on the preprocessed data, then take the output probability density functions outputted by each expert, multiply them together and renormalize.

Implementation

I’ve realized that I haven’t said much of implementation details thus far in this blog, which is kind of an oversight on my part. I’m implementing everything in python using the library Theano.

Theano, in their own words, is a Python library that allows you to define, optimize, and evaluate mathematical expressions involving multi-dimensional arrays efficiently. Rather than using python’s native syntax for mathematical operations, which evaluate in a declarative manner (e.g. if a and b are integers, a + b will evaluate to an integer immediately when the line of code is executed), they rework python into a relational language, where mathematical operations build a computation graph, which can be optimized more easily than code (e.g. if a and b are theano variables, a + b will be another theano variable corresponding to an addition operation). Instead of holding values (like variables normally do in python), Theano variables are just placeholders, which can be specified as inputs or outputs to theano functions, which can be executed just like native python functions. I suggest anyone interested in high performance computing or deep learning check out the Theano tutorials for more information.

On top of Theano, many libraries exist implementing deep learning techniques. In order to maximize the amount of freedom I had over my own model’s structure while still skipping the work involved in implementing LSTM layers from scratch, I use a lightweight library, theano-lstm, which implements standard neural network layers and LSTM layers, and implements a few different gradient descent optimizers for use with them (I use AdaDelta in my experiments because that’s the one I like, there’s not a huge amount of functional difference between different optimizer algorithms).

Training

Implementing this process during training was easy. I had Theano variables for generated probabilities as instance variables in my expert model classes, so I could easily instantiate multiple models, then instead of using the train functions for each one separately, take that generated distribution vector for each model, convert it into a vector of probabilities over absolute pitches (which was mostly just shifting the values for the two relative pitch models until they matched up with the absolute pitch models), then take the weighted elementwise product (where weights are exponents) and divide each element by the total of the new product vector.

(The training process is actually done in minibatches, so all of the vectors are actually lists of vectors (matricies) with the same operation done to each vector, but it’s easier to conceptualize without batches).

Generation

Generation becomes much more difficult when the product model is taken into consideration since, instead of each expert sampling from its own output distribution to figure out which note to feed back into itself for the next timestep, we need to sample from the product distribution, which means that the sampling process needs to go within the body of the generation loop. Since Theano variables don’t actually hold values, using python loops to repeat computation won’t actually do anything, so Theano uses analogs to lisp map, fold and scan to denote loops. For reasons that are beyond the scope of this blog post, those functions don’t behave well if state (in the functional programming sense) is introduced, and random numbers introduce state, so debugging the generation process for the base GenerativeLSTM class I wrote and the product model was a bit of an adventure.

Results

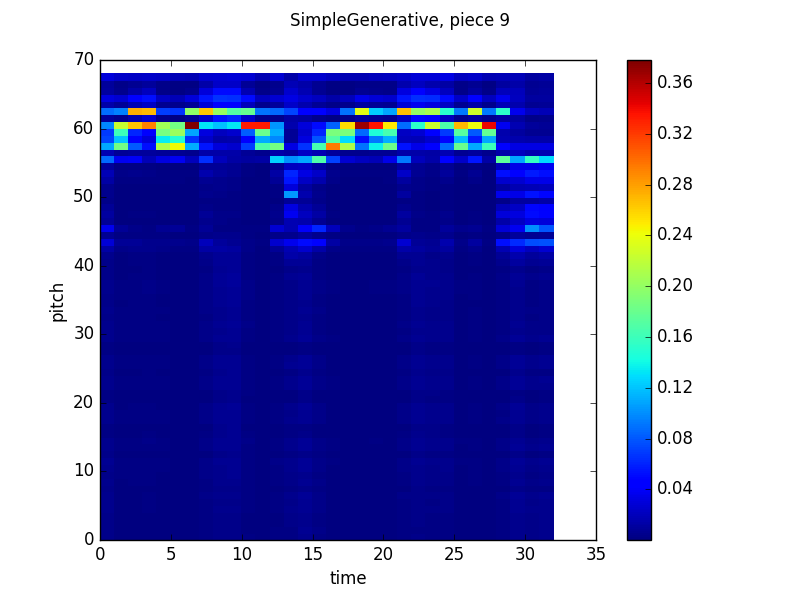

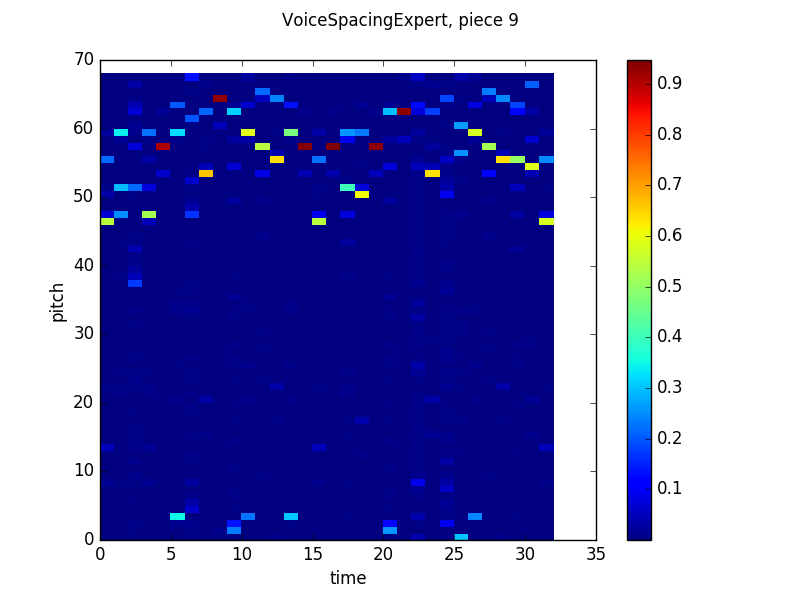

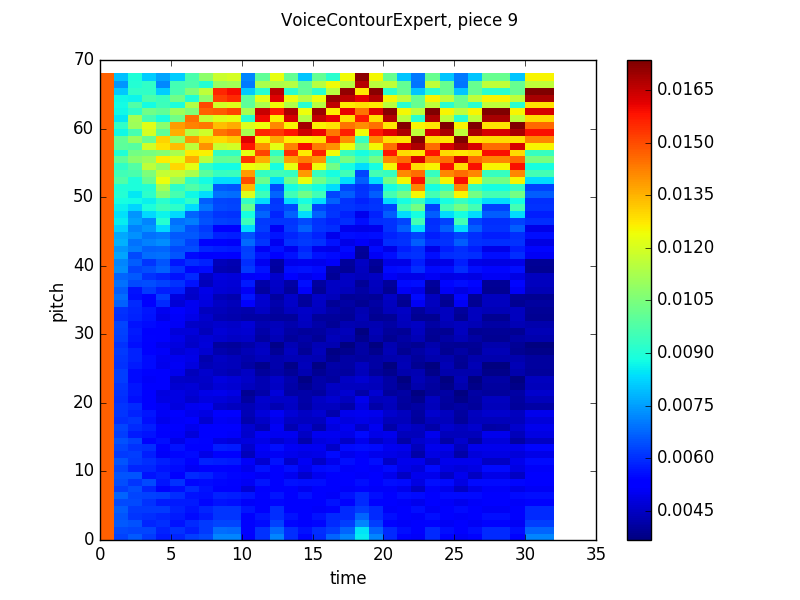

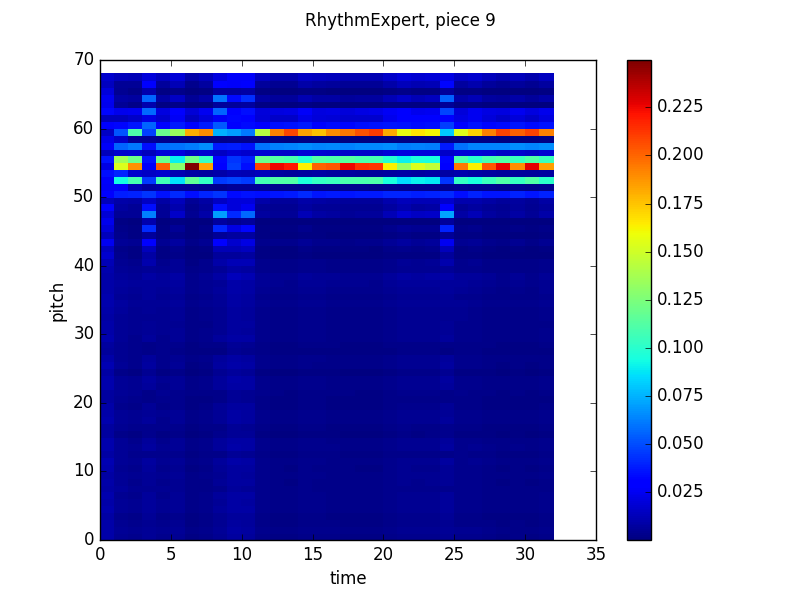

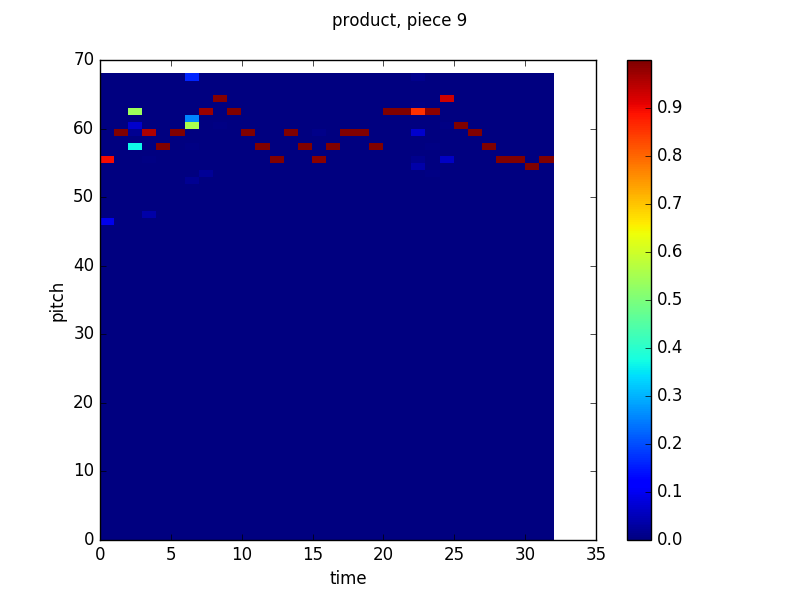

In the end, though, everything worked out. Here are some pretty pictures of the way the product looks using the same graphing technique (X axis is time, Y axis is pitch, color indicates probability according to the scale on the right) as the previous two posts:

Simple Generative output:

Voice Spacing output:

Contour output:

Beat Position output:

All of these look pretty similar to the models’ outputs discussed in the last post. While each model’s predictions (the notes it gives higher probabilities to, which are represented by warmer colors) are pretty scattered. When we take the product though, things settle down considerably:

Out of curiousity I also recorded the weights for the relative experts

- Simple Generative: 1.4476759800109495

- Spacing: 1.8992706034951548

- Contour: 1.0340933143428621

- Rhythm: 1.3123701737615971

Since the final distribution is normalized, the absolute values of these weights don’t mean anything, but their relative values tell us how much the product model “listened” to each expert. The takeaway from this is that none of the experts were unhelpful, since the weights are all relatively close, but the output from the spacing expert’s output was a more reliable predictor of the actual notes than any of the other models. That said, the product model’s prediction error is significantly lower than any of the individual models (compare 3405 negative log likelihood of generating the validation minibatch for the spacing expert to 776 for the product expert).

In fact, the product model is able to predict most of the notes with almost perfect certainty. While for a normal prediction problem that would be excellent, for a system I want to be at least original if not creative, perfect prediction accuracy is less desirable. There are two ways I’ve thought of to avoid this sort of problem. First, I can expand the training set to include four part harmony that wasn’t written by Bach. That may allow a mixing of styles, since the model won’t know that there is a fundamental difference between excerpts from Bach as compared to excerpts from other composers. Second, I can include some number of random numbers in the input vector to each expert model. This is much easier than finding more data, since it’s just code, but may decrease the quality of results because the models may fit better to trends in the random inputs than the actual ones. Regardless, I plan to try both methods in the coming weeks.

But Sam, Where’s the Music?

So far, I haven’t implemented a method to generate four part harmony from scratch yet, this model just predicts a single voice given the other voices. My plan is to generate a first voice using the contour and beat experts first, then generate other voices using the product model. That said, a few examples from different points in the training process (0, 100 and 200 minibatches in, respectively) are below.

A few disclaimers: The model currently articulates (starts a new note) each timestep, which here is an eight note. That’s why the melody seems to just be straight eighth notes. Second, these are midi files, so they are synthesized from a series of off and on signals and usually don’t sound much like real instruments or performers. For contrast, the last track is a real piece by Bach from the training set (BWV 269).