DeepBach

1/29/17

As promised in a previous post, I wanted to write a summary of the DeepBach paper, published in December, which achieves a result similar to what I want to achieve with this project. This article saw some news coverage when it was published, so it may sound familiar. It is currently, as far as I know, the state-of-the-art model for generating Bach-like music.

Bach’s chorales present a good dataset for automated music generation research since it consists of a large number of short pieces with a fairly homogeneous structure. Five previous attempts to generate music based on Bach’s chorales include Ebcioglu’s 1988 rule-based model, Hild et al’s 1992 neural network model, Harmonet, Allan and Williams’ 2005 hidden Markov model approach, Boulanger-lewandowski et al’s 2012 RBM approach, and Liang’s 2016 LSTM model Bachbot. These approaches transposed chorales into a common key, generated voices separately and generated from left to right, forwards in time. Hadjeres and Pachet, the authors of this article, propose a model that avoids those constraints.

They represent notes in a chorale similarly to older models, with a list of pitches representing each voice, a list of timestep subdivisions (whether each timestep is on the first, second, third or fourth sixteenth note of a beat) and a list of whether a beat is held as a fermata. Their goal is to minimize the negative log probability of outputting exactly the four voice lists, given the timestep subdivisions, fermata information and a vector of parameters, \theta. They approximate this probability by summing the probabilities that their model outputs a single correct note given all of the other notes in the piece over all the notes in the piece.

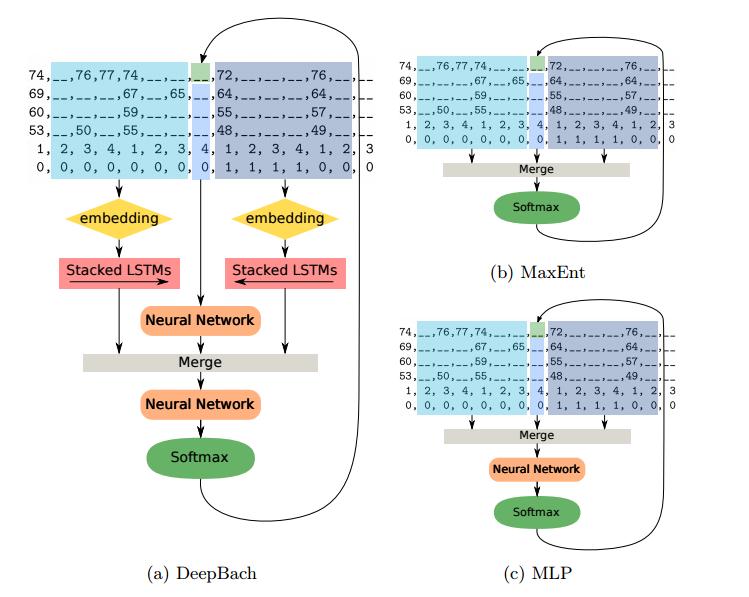

Model

The model they come to is three neural networks, two recurrent, one feedforward, in parallel, followed by a fourth neural network to merge the outputs. One of the recurrent neural networks takes as input an embedding (using Keras’ embedding layer) of the notes sequentially in order from 16 timesteps before to the note to predict, while the other takes as input an embedding of the notes sequentially in reverse from 16 timesteps after to the note to predict. The feedforward network takes the raw values of the notes concurrent in other voices with the note to be predicted. The fourth network takes as input the outputs of the three other networks, merged (using Keras’ merge layer), and outputs a prediction of the note, which is turned into a probability distribution over possible notes using a softmax layer. Their network is trained using backpropagation with the adam optimizer without dropout.

Rather than generate notes in order from start to finish, they use Gibbs sampling to generate their pieces. That means they start with a piece of a given length with all of the notes in each voice initialized to random values, then iteratively choose a note, use their model to predict what it should be using the surrounding notes, change the note’s value to a sample from that prediction, and repeat an arbitrary, large number of times. They reduce the amount of time the generation process takes by parallelizing it on a GPU. They found that they could update up to 32 notes’ values simultaneously without overlapping note contexts.

This model and experiment are quite similar to what I am doing — we both are trying to generate Bach, we both are using recurrent neural networks to do so, we both use a synthesis of several neural network predictions and aim to end up with a steerable model that can harmonize existing melodies and generate from scratch without retraining. There are also several differences — I use preprocessing and one-hot encodings rather than encoding neural network layers, I use input encodings that make use of relative pitch data to avoid key problems, they transpose each chorale into all twelve keys, I use a product of distributions rather than a merge layer to synthesize predictions and I generate voices sequentially rather than using Gibbs sampling.

Evaluation

Their evaluation metric consisted of a listening test, conducted online, where participants would listen to original chorales and harmonizations of existing melodies generated through three methods: a MaxEntropy model (a neural network with no hidden layer and a softmax activation), a MLP model (a neural network with one hidden layer), and their DeepBach model. In the first stage of their experiment, they present the original Bach harmonization of a melody and each method’s harmonization and ask users to choose which one sounds the most like Bach. As expected, DeepBach outperformed both of the other methods, but underperformed the actual Bach (see their paper for the actual graphs and discussion). The second experiment they conducted asked participants to decide whether a given chorale was written by Bach or not. DeepBach again outperformed the other two methods, but underperformed Bach.

While I like the evaluation metric they choose, I think the benchmark they measure against, a simple model they built using an existing technique, rather than the previous state of the art model (which they identified in their introduction as BachBot), is questionable.

The third metric they used was plagarism detection. They measured plagarism in a piece by the longest sequence of notes that appeared in the generated piece that also appeared identically in the training set. They found that reharmonizations tended to have more plagarism than unconstrained generation, but both had less plagarism from the training set than a test set of actual Bach. They also went through three generated harmonizations and hand-labeled plagarism

I want to use a very similar evaluation metric, with a listening test and plagarism detection system, and this paper offers a very good experimental framework, so I plan on using a good deal of this paper’s experimental methodology in the coming weeks.