Some Thoughts on Genre in The Incredibles

5/17/17

It’s May now, and I’m done with classes! Commencement at Oberlin is next Monday, so I have some free time, and I decided to write a post. Rather than spend more time on my honors research, I figured I’d go into something else I’ve been thinking about and researching lately, which is Michael Giacchino’s score to the Disney Pixar film The Incredibles. I wrote a paper for a music theory class on this topic, but I had a lot of thoughts about the music that didn’t fit nicely into a paper, so I’m going to try to fit more content into a less structured blog post.

Spoilers follow, so if you haven’t seen the movie, you’ve been warned.

The Incredibles is a movie about Bob Parr, who is the superhero Mr. Incredible, his family, who also have superpowers, and their experiences saving a world that doesn’t really want to be saved. The film opens in a documentary style, with shots that look they’re taken from interviews with the main characters, then goes into the first scene. This scene, which we’ll spend most of this post discussing, shows us Mr. Incredible and Elastigirl, his future wife, on the day of their wedding fighting crime and doing good.

Towards the end of this scene (after the end of the video above), though, Bob saves a man attempting suicide. The film tells us that Mr. Incredible “didn’t save my life, he ruined my death!” which launches us back into a documentary style discussing the series of lawsuits surrounding superhero activity that forces heroes to stop being heroic. The government quietly relocates the former superheroes and settles them into normal human life.

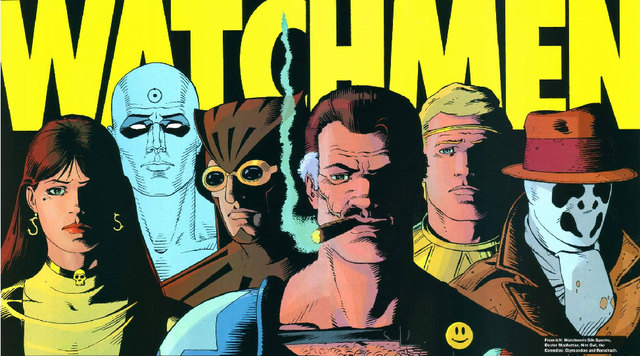

Audrey Anton finds this plot reminiscent of Alan Moore’s Watchmen, and, more generally, the loss of innocence in the comic book medium. She views the dialogue between the two texts through a Nietzschean lens and claims that The Incredibles exists as the liberal humanist response to Nietzsche’s claims about the role of the übermensch (which is pretty much what a superhero is) in society. Contrary to Nietzsche, the “moral” at the end of The Incredibles is that everyone should be free to be themselves and use their abilities to the benefit of humanity, but not seek fame for doing so.

A related dialogue between realism and idealism manifests itself throughout the film. Mr. Incredible is a distinctly “Golden Age” character living in a “Bronze Age” world (For those unfamiliar with comics history, the Golden Age was the first era of comic books in the 30’s and 40’s, and the Bronze Age was the second resurgence of comics in the 70’s and 80’s, see this timeline for more details), and his motivations largely stem from nostalgia for the glory days when things were simpler and people adored him for doing what he loved.

Michael Giacchino’s score for the film paints this nostalgia perfectly. We, as the audience, are treated to a ridiculously stylish musical aesthetic in the first scene of the film (“The Glory Days”), which doesn’t really return until the full family is fighting near the end. Instead, the middle of the film uses a more subtle style, focused on winds and strings rather than brass and percussion. The one exception to this trend is a montage in the middle of the film showing Mr. Incredible employed by Mirage, getting back into shape, accompanied by a musical track called “Life’s Incredible Again.”

These changes in style correlate perfectly with the moral ambiguity of the problems that the characters are facing. When the sountrack is dynamic and stylish, the characters are at the top of their game with clear purpose and a strong sense of good and evil. When the soundtrack is subtle and muted, the characters are forced to face more difficult and realistic problems.

What I, as a music theorist, am interested in is how that first style evokes nostalgia so well. Through the rest of this post, I’m going to look at the first scene, The Glory Days, and adopt a music semiotic lens (music semiology is the study of musical signs and symbols) to figure out where that style comes from and why it is so nostalgic. In particular, I’m going to discuss a few genre references and music-image mappings that give this score its unique character.

Genre References

This movie, like many Pixar films, is oozing with style. And like most style, it’s not entirely original. The music for the first scene, a track titled “The Glory Days” in the soundtrack, draws from three big stylistic tropes, Spy Music, Superhero Music and Love Music. I want to go into each of these, figure out where the style comes from originally and identify what musically evokes that style.

Spy Music

The first genre reference we will investigate is with spy media, like The Pink Panther or Get Smart!. Though The Incredibles isn’t a spy movie and has a very different plot and visual aesthetic from spy movies, the “spy music” style is really the center of the piece.

Spy music was established in John Barry’s scores for 1970’s and 80’s James Bond movies, starting with On Her Majesty’s Secret Service in 1969. OHMSS features heavy brass scoring, fast tempos, minor keys and jazz associations, with glissandi and muted trumpets, and central to the feel is the juxtaposition of a 3+3+2 subdivision in the bass with a slow melody in four.

The origin of this style was not with John Barry’s music, but with Monty Norman’s work on the first Bond movie, Dr. No in 1962. That film is the origin of the well-known James Bond theme song, which uses a surf guitar alongside the orchestral jazz texture to complement Sean Connery’s depiction of Bond as simultaneously “classy” and “cool”.

That James Bond theme, though, has a bizarre past. It notably begun its life as a song from Norman’s failed broadway adaptation of A House for Mr. Biswas by V.S. Naipaul, where the melody was played on sitar rather than surf guitar.

There’s actually a really weird song that Monty Norman wrote explaining this origin story. It might be the worst piece of music I’ve ever heard, so listen at your own risk.

But enough of that. Back to The Incredibles.

Giacchino’s score mimics several of these characteristics.

First, the instrumentation, orchestra with expanded brass, and minor key of the piece are similar to the older Barry film scores.

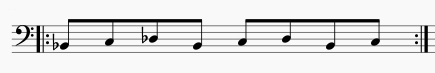

Second, the 3+3+2 rhythm is everywhere in the piece. There’s a consistent bass ostinato that accompanies any shot associated with the car chase going on and almost every other melody embodies that subdivision to some extent.

“Chase” theme ostinato

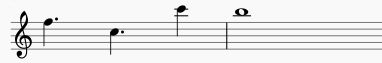

Third, the melodic figures and performance style evoke jazz. Two other melodies that appear several times through the piece, the “Mr. Incredible” theme and the “robber” theme draw attention to the tritone in a jazzy way and are played with scoops and falls that are essential to the Big Band style.

“Mr. Incredible” theme

“Robber” theme

The use of spy music, though unusual for a superhero movie, was decided on extremely early in the film’s production. The original teaser trailer was accompanied by the Propellerheads’ version of the OHMSS theme. Brad Bird, the director, asked John Barry to score it, but Barry refused, since he wasn’t interested in writing spy music any more.

So why was Bird set on spy music in a superhero movie? Two explanations come to mind:

- It dates the score. Big band jazz was popular in the 30’s and 40’s, which is when the Golden Age of comics took place.

- Spy music is cool and suave; James Bond can be in grave danger and still look classy, which highlights the nostalgia Bob feels for simpler times when he was cool and universally loved for being a hero.

Superhero Music

While “Spy music” covers many of the genre references in the piece, it doesn’t really get at the Mr. Incredible theme sufficiently because the theme is also tied to the “Superhero music” style.

Superheroes have a unique situation, among characters originally from a written medium, of being conceived with extremely strong visual aesthetic – each hero has a unique outfit, icon and art style to differentiate them from other heroes. For instance, how many of the superheroes in this image below can you identify from just their most fundamental visual style?

Film and TV composers have pretty consistently interpreted the musical extension of that aesthetic to be the theme song.

Side Note: I think it’s really interesting that theme songs are heavily related to leitmotifs, which really come from Wagner. Wagner was good friends with Nietzsche, and Siegfried, the hero of the last two operas of Wagner’s Ring cycle, is often used as an example of Nietzsche’s übermensch. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that theme music fits with superheroes so well.

Superhero TV adaptations like the 1966 Batman or 1967 Spider-Man TV series had iconic theme songs that became closely associated with their starring heroes, and stayed in the public consciousness even after their TV shows stopped being aired (for instance, my roommate who has never seen 1967 Spider-Man series recognizes the theme song melody).

These theme songs share some of the jazzy characteristics of The Incredibles superhero theme music, like focus on the tritone or a blues chord progression (which draws another tie between superhero music and spy music), but do not mimic the more romantic “heroic” associations with the ascending fifth and sixth leaps in the Mr. Incredible theme. I found more of those sorts of ideas in John Williams’ score for Richard Donner’s 1978 film Superman.

Evoking these musical ideas in this part of the piece helps to create a sense of nostalgia for simpler times, much like Bob is feeling. Donner’s Superman film presents a nostalgic interpretation of the Superman mythos that is a generation out of date in 1978, closer in style to the Golden Age comics of the 30’s or 40’s. Further, The Incredibles was released in 2004 and marketed towards children whose parents would have grown up in the 70’s and 80’s with movies like Superman, making these musical ideas nostalgic for them.

Love Music

There’s one more genre reference that I found worth discussing in this scene, and that’s the “Love Music” style at the end of the “Glory Days” scene. Giacchino uses what I think are two separate references, one to the love music of superhero movies, and another to the love music of spy movies.

The first style occurs as the scene introduces Elastigirl, Mr. Incredible’s future wife. The music features high strings and harp, which is unrelated to the Superhero music or Spy music we’ve already talked about, but still feels to me like a genre reference.

The idea of “Love Music” that sounds like this in film scores is pretty common. A good example is the love theme from The Godfather

I think Giacchnio borrows this style more directly from John Williams and the 1978 Superman score again (as the first blockbuster superhero movie, it’s had a lot of influence).

So where did this style come from? Niether John Williams nor Nino Rota invented it. The earliest thing I can find that sounds stylistically similar is Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet.

I think there’s another reference going on in this music at the end of the clip, specifically as Elastigirl is walking off from rooftop to rooftop. The style changes slightly to include muted trumpet, which I think relates to a more Noire-Jazzy love music. For example, Jerry Goldsmith’s score for Chinatown

I clearly have a lot of feelings about this movie, and have probably said enough at this point, so I’m going to split this into two posts for the sake of readability. The next post will talk about music-image mappings in the piece and will probably be done within the next week.