Sonic Primitives

Hi! Sorry I don’t post much. I now have a real job and spend most of my time on that. Also I finished my honors research, so I didn’t have too much to write about until recently.

Last week, I discovered a wonderful twitter account that posts art generated from images using Primitive.lol by Michael Fogleman. Since following it, I have been bombarded with beautiful images of shapes arranged to resemble real things.

160 triangles. https://t.co/NlkLNPk6AP pic.twitter.com/q9m1wXQ6zR

— PrimitivePic (@PrimitivePic) November 29, 2017

I really like this art style for two reasons.

First, it exists at the boundary of discrete and continuous forms, kind of like pointillism. The shapes that make up the art are simple, atomic and not particularly representational, but as the number of shapes increases, the number of overlapping shapes and colors skyrockets and begins to approximate a continuous form like a bird. It kind of reminds me of calculus, where Reimann sums use infinitely many rectangles to approximate all sorts of other curved shapes.

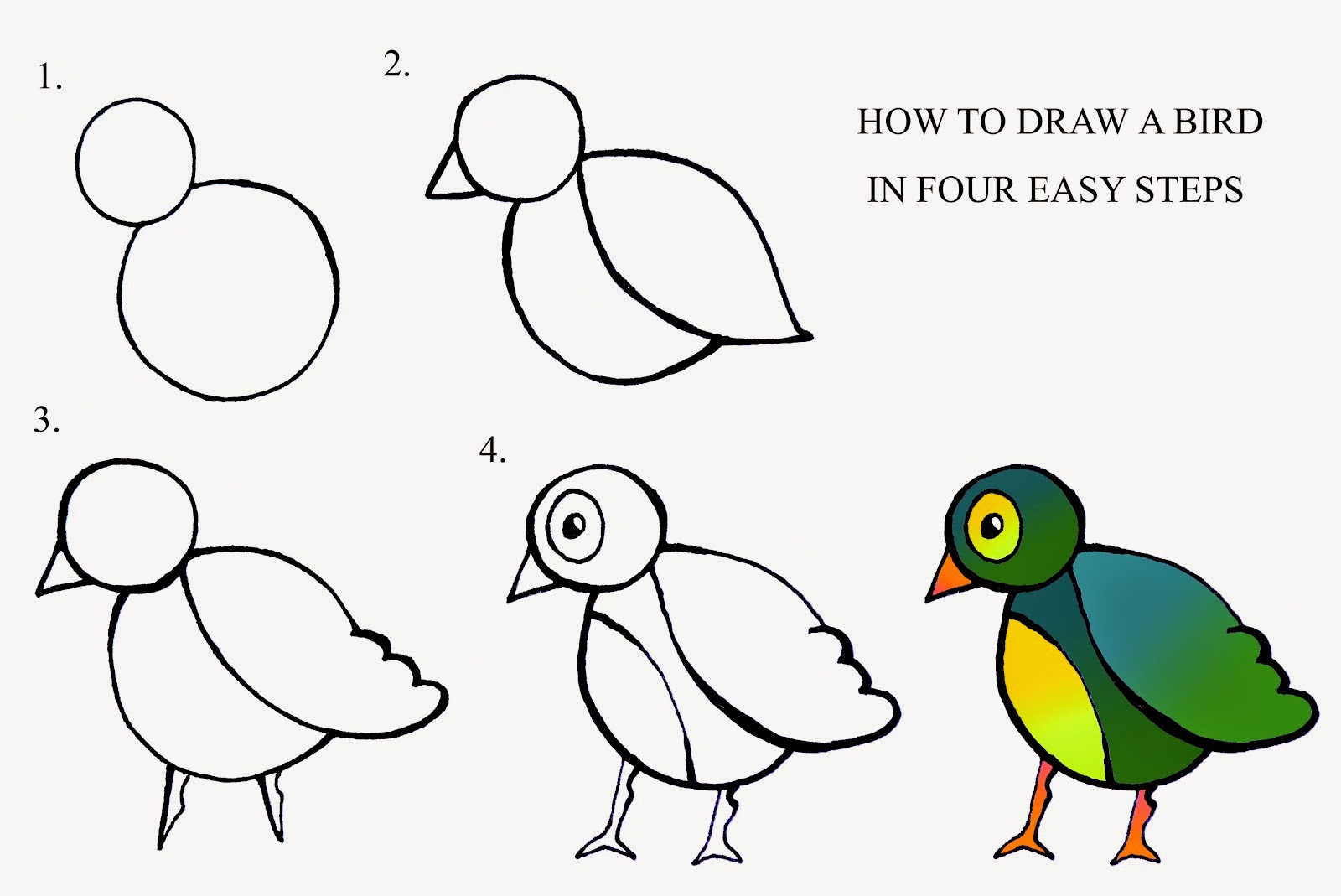

More importantly, though, at least for me, these images are cool because they approximate continuous shapes with discrete shapes without relying on a human’s impression of how the shapes should be used. They capture a more random, almost alien idea of how shapes fit together to approximate the world. If you ask a human to do that, they won’t end up with the bird image in the tweet above, they’ll end up something more like this:

Since I’m a musician, I immediately wondered what this technique would look like for sounds instead of images. Before discussing how I did that, it’s important to pin down exactly how Fogleman’s program works.

The Original Algorithm

Fogleman’s algorithm works as follows:

- Create a synthetic image with the same dimensions as the original, that starts blank.

- Create a new shape, place it on the synthetic image, then adjust that shape until its position, size and color increase the similarity of the sythetic image to the original image as much as possible.

- Repeat step 2 as many times as the user wants.

The challenge is where to put the shape. Fundamentally, this is a search problem with several dimensions: X position, Y position, rotation, width, height, and red, green and blue color, where the goal is to find the values of the parameters that maximize the “closeness” to the original image. It’s a difficult search problem because image similarity is measured at the pixel level, and since pixels are discrete, the function mapping shape parameters to distance from the original image is discontinuous as well.

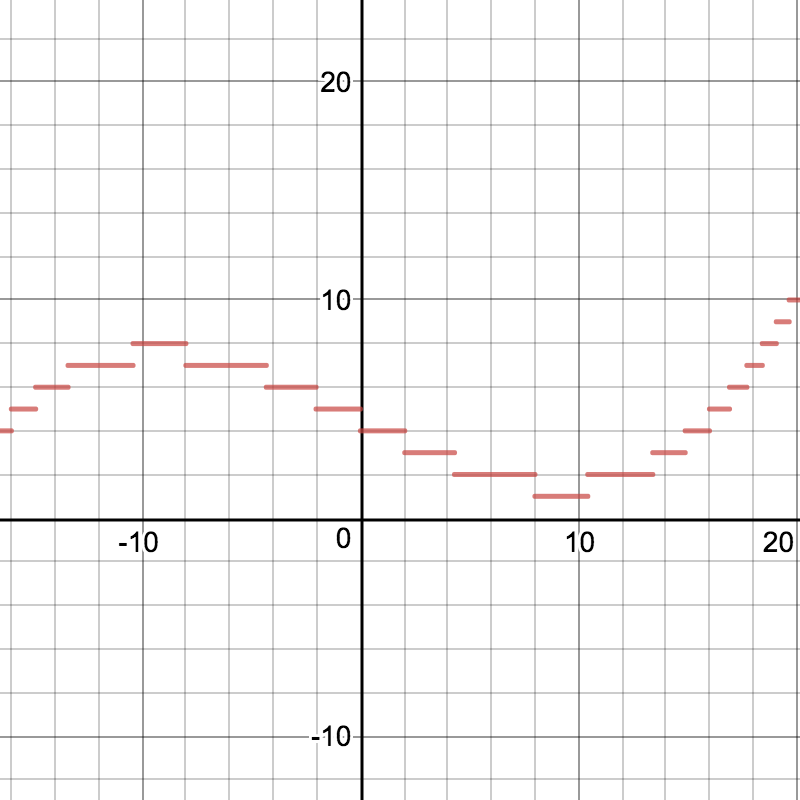

Despite the discontinuity of the search space, there are still ways that we can find good parameters without exploring all of the different potential combinations. The key observation is that, while the search space is discontinuous, it’s only locally discontinuous, and has contour in the same way as a step function. For search problems, it’s often helpful to use a physical metaphor. From now on, a “position in the search space” corresponds to a set of values for the parameters and the “height” of a given position is how similar it makes the synthetic image to the original, where higher is closer.

The method that Fogleman uses is hill climbing, which is an algorithm that starts at a random position in the search space, looks at the height of positions surrounding it and changes its parameters to the highest, “climbing” the hill. This algorithm is guaranteed to find a maximum, which is a peak without higher points around it, but can get caught in local maxima and isn’t guaranteed to find the global maximum, or highest point in general. To avoid getting stuck in one of these local maxima, we make it stochastic and choose which direction to go with a probability proportional to its height, which adds a random chance that the algorithm will instead go downhill, in the hopes that it will eventually either return to where it was or find a higher peak.

My Version

I wanted to try to apply this algorithm to sounds and see what it did. I think there are pretty good sonic analogues to all of the concepts in the algorithm:

- Image files become audio files

- The color of a pixel becomes the amplitude of a single sample

- Shapes become sound waves

- The position, size, color and rotation parameters become start time, end time, frequency (pitch) and amplitude (volume)

As a result, we end up with a pretty clear procedure for making sounds out of “sonic primitives”. The coolest part, at least for me, is that the algorithm is still guaranteed to converge to an identical sound after an infinite number of iterations by Fourier’s inversion theorem.

I programmed the algorithm pretty quickly in python, using numpy to speed up the synthesis process. At this point, I only worked with sine waves, but it wouldn’t be too difficult to implement square, triangle or sawtooth waves as well. Here’s my implementation.

As expected, the hill climbing algorithm was a little finicky. Initial attempts ended up with either sound waves that were too small to change anything or too large and actually increased the difference between the synthetic sound and the real one. The trick that got it to work was 500 iterations of stochastic hill climbing followed by 500 iterations of non-stochastic hill climbing for each new wave. The stochastic phase would avoid local maxima and the non-stochastic phase would find the closest maximum. In effect, if the stochastic part of the climb found a poor wave, the non-stochastic part would reduce its amplitude (volume) to zero, and if the stochastic part found a good wave, the non-stochastic part would fine-tune it.

Here are two of the experiments I did. In both playlists, the first track is the original, and the following ones are approximations, where the number is the number of sine waves used.

The original sound in this experiment is from this website.

While as a programmer and an engineer I am most proud of the last “Hello” track, since I can hear the words, as a musician I am much more interested in the 200 wave approximation of Piano2. Like the images, it represents a computer’s semi-random impression of what is important in the sound, without the influence of a human’s ear or cognitive musical biases. As a result, it allows us to hear more of the nuances of the piano’s timbre and texture than the original does, because we can’t place it into the mental construct of “Piano”.

These ideas about music and sound are nothing new. The idea of creating sounds by adding sine waves together, called additive synthesis, is one of the fundamental ideas behind electronic music. Spectralist composers of the late 20th century like Tristan Murail and Gerard Grisey summed together sounds to approximate recordings, however they used Fourier analysis to split up the sounds into their component sine waves, then orchestrated the sine waves to create an acoustic depiction of the recorded sound.

From another area of 20th century music, the idea of constructing sounds out of random clouds of smaller components is a big theme in the music of Georgiy Ligeti and Iannis Xenakis. Xenakis, in particular, would probably have been fond of this way of constructing what he called “second order sonorities” or sounds built out of other sounds. At some point, I’ll post the thesis I wrote for my music major, which was on his music.

Anyway, feel free to clone my github repo and try for yourself! Be warned that each of the hundreds of sine waves may take upwards of a minute to be optimized. There may be use for a GPU to speed up the computation, but I am fine waiting, for the moment. If you are interested in my work but aren’t a programmer, send me an email at the address in the sidebar! If there’s interest, I will look into making an application like Primitive for non-programmers to use.