User Interfaces, Metaphors and Midi Keyboards

I’ve had some free time lately (I recently left my job at RTI and am starting a PhD at Indiana University), so I’ve been reading and programming for fun again. Some of that reading and programming tied itself nicely into a coherent project that I’ve written up below. If you just want to skip to the programming, I’ve made a webapp available here.

User Interfaces

At work a few months ago, I was introduced to the idea of user-centered design (UCD). The gist is that when humans interact with technology, the interface should be designed and engineered around how humans want to use the product, and not force them to adapt their behaviors to accomodate. When software is designed with users in mind, the users are more likely to want to use the software and the software is more likely to be widely adopted.

The aspect of this idea that got me thinking, though, is how UCD can be applied to interfaces other than UI for software products. APIs, software packages and frameworks, even code organization within a project can be treated as user interfaces that one software engineer is designing for future software engineers, and can be built with use cases and user testing in mind to make development easier in the future. If software works the way people expect it to work, it is easier to use.

UCD can be taken even further, though. All you really need to apply it in an arbitrary context is a user who is trying to accomplish something, a tool that works towards that end and an interface between them. As a musician, my favorite interface is a musical instrument. While musical instruments are, to some extent, limited in their design by the acoustics of the instrument itself, there’s still plenty of room for a designer to make decisions on how the musician interfaces with the instrument.

Musical instrument interface limitations also vary greatly from instrument to instrument; for example, piccolos must be small and held by the mouth horizontally, so there’s no way to build a piccolo that doesn’t involve the musician’s hands being close to their face, while pipe organs can have virtually any interface, so they use the most familiar interface possible, keyboards, buttons and levers.

(Revision 6/25/19: In hindsight, this section isn’t quite correct. I’m not interested in applying UCD to musical instruments, I am more interested in applying ideas from interaction design research on metaphors and affordances. I’m going to leave the text as-is, though, since we’re all a little wrong sometimes.)

Metaphors

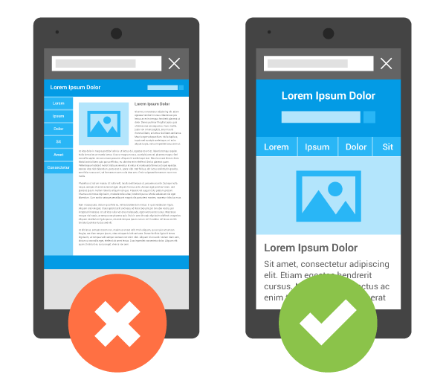

User interfaces, by virtue of being designed, are always at least one layer of abstraction away from what they do. For instance, a computer program will not have the user determine literal voltages to send to the CPU, they will have some interface, which could be graphical buttons and menus or function names from a library. For example, the icons below are familiar, instantly recognizable symbols for extremely complicated program behavior.

![]()

Whether that symbol is a pictogram on a button or a function name, the interface is a symbolic representation of the functionality. The best user interfaces make use of abstract metaphorical relationships so that the user doesn’t have to worry about the implementation details. For example, a video player may make use of the metaphor “Time moves from left to right” in order to have a bar which allows the user to navigate to a specific point in time in the video.

(Side Note: When I refer to metaphors here, I’m using a definition that comes from George Lakoff and Mark Johnson’s book Metaphors We Live By, which discusses conceptual metaphors and their role in our language and culture).

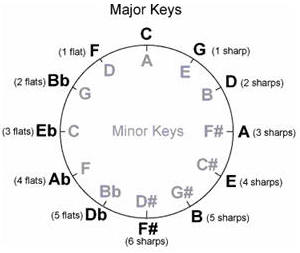

What metaphors tie musical instruments to their function? Usually, there is some mapping of pitch onto distance that is a result of the physical acoustics of the instrument (e.g. a guitar will produce higher pitches if the guitarist’s finger is on a fret closer to the body). The theremin uses a higher-order metaphor, it maps voltages onto pitches (via a voltage-controlled oscillator), and maps the distance between the performer’s hands and the antennae onto voltages (via capacitance of the hand-antenna system), allowing the performer to control the pitch using the distance between their hand and the instrument.

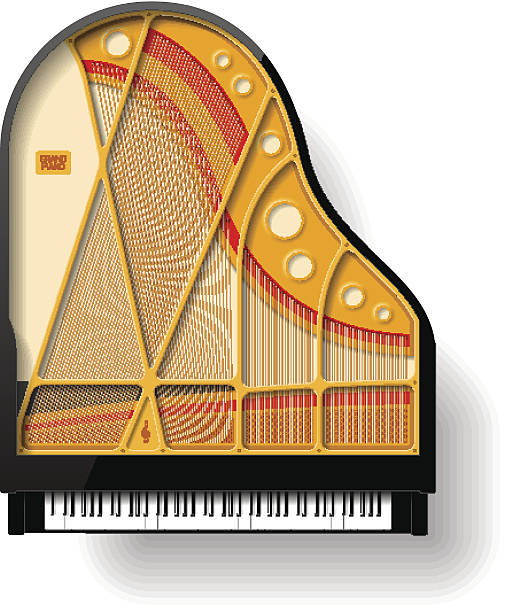

With more mechanically complex instruments, though, like keyboard or electronic instruments, that doesn’t need to be the case. For instance, one could imagine a piano that, instead of arranging the strings from longest to shortest, used some other ordering like the circle of fifths. A piano built like that would be extremely difficult to play for trained pianists – some pieces may become physically unplayable – but would make a whole new musical space accessible.

MIDI Keyboards

Online MIDI keyboards (like the one here, here or here) are some of the furthest-abstracted interfaces for musical instruments. The sound comes from electronic speakers, which are controlled by a digital synthesizer. That synthesizer is in turn controlled by an application running inside a web browser, over the MIDI protocol. The pianist interacts with that web application via either their keyboard, where keys are mapped onto virtual piano keys, or their mouse, which is a significantly different interface.

None of those interfaces are set in stone, and we can imagine lots of different ways to construct their inherent metaphors. For example, we could have different keyboard keys map to different notes, use the shift key to specify accidentals or octave in a way that is natural on a computer keyboard, but not on a piano or use key presses to map to something else besides a note.

That last idea is the most interesting to me, since the correspondance between key presses and notes is more a relic of physical instruments (and the skills of keyboardists) than any technological limitation. Many MIDI synthesizers already have settings for percussion instruments, where keys do not correspond to pitches, but are mapped onto an arbitrary ordering of percussive sounds (while those are technically pitched, their pitches are not their primary feature).

One alternative mapping of music onto physical space called the Tonnetz comes from Neo-Riemannian musical analysis. While how it works is beyond the scope of this blog (Generalized Musical Intervals and Transformations by David Lewin is the book to read), the important idea is that we can re-imagine musical space where pitch classes are close to one another based on tonal harmony and voice leading, not frequency. The shape of the space that results is pretty neat, it’s visualized in the gif below.

To explore these ideas further (and practice with react) I built an online MIDI keyboard that flexibly allows for different mappings from keys to musical behavior. I used webmidi to handle the MIDI integration, so you can use input from a USB MIDI keyboard to control it, as well as use any MIDI synthesizer running on your computer for output. If you’re on Windows I’ve had success in Firefox using the WebMidi plugin, if you’re on mac, you may need SimpleSynth. On Linux, I’ve had success with QSynth and Jack, but it’s a little more difficult to set up correctly. I used PureCSS and followed this tutorial to make the visual interface.

Check it out here!

These ideas and implementation are also definitely a work in progress (I’d like to iterate on some of these designs so they better convey the ideas behind them). If you have any comments or recommendations, feel free to let me know at the address in the sidebar!