Can Neural Networks See Cuteness?

I’ve been doing a lot of cool things recently which haven’t really made it to this blog, but I promise they’re coming! In fact, this post is one of them, it’s based on a paper I wrote for a class last year. I’m going to start by explaining one of the important ideas we discussed in this class, then go on to explain an experiment I did based on these ideas.

TL;DR I was wondering whether neural networks trained to detect cute things actually understand cuteness. I did some experiments and found that the answer was “yes…sort of?”

Hofstadter and Google Translate

In the class I took last year, we talked about intelligence, artificial intelligence and how human and machine intelligences interact. One week, we read a piece in the Atlantic by Douglas Hofstadter.

In this article, Hofstadter discusses machine translation. He argues that despite major advances, there is something deeply lacking in machine translation systems like Google Translate. Despite producing reasonable translations which convey the gist of a sentence, it doesn’t really understand what that sentence means, or how to preserve that meaning across languages. To quote Hofstadter,

[Google Translate is] familiar solely with strings composed of words composed of letters. It’s all about ultrarapid processing of pieces of text, not about thinking or imagining or remembering or understanding. It doesn’t even know that words stand for things. Let me hasten to say that a computer program certainly could, in principle, know what language is for, and could have ideas and memories and experiences, and could put them to use, but that’s not what Google Translate was designed to do. Such an ambition wasn’t even on its designers’ radar screens.

What Hofstadter is getting at is that Google Translate doesn’t understand language because that’s not what it was built to do. The engineers at Google aren’t trying to create a robust intelligence, they’re trying to create a translation tool. All it is supposed to do is convert text in one language into similar text in another language.

If two artificial agents come up with the same translation, though, one which is “really” intelligent and another which is merely converting text, does the difference matter? Plenty of scholars (like John Searle and Herbert Simon) have written a lot about this question. I’m not going to discuss their answers in this post. Instead, I’m going to dig deeper into what concepts an artificial agent can really understand today.

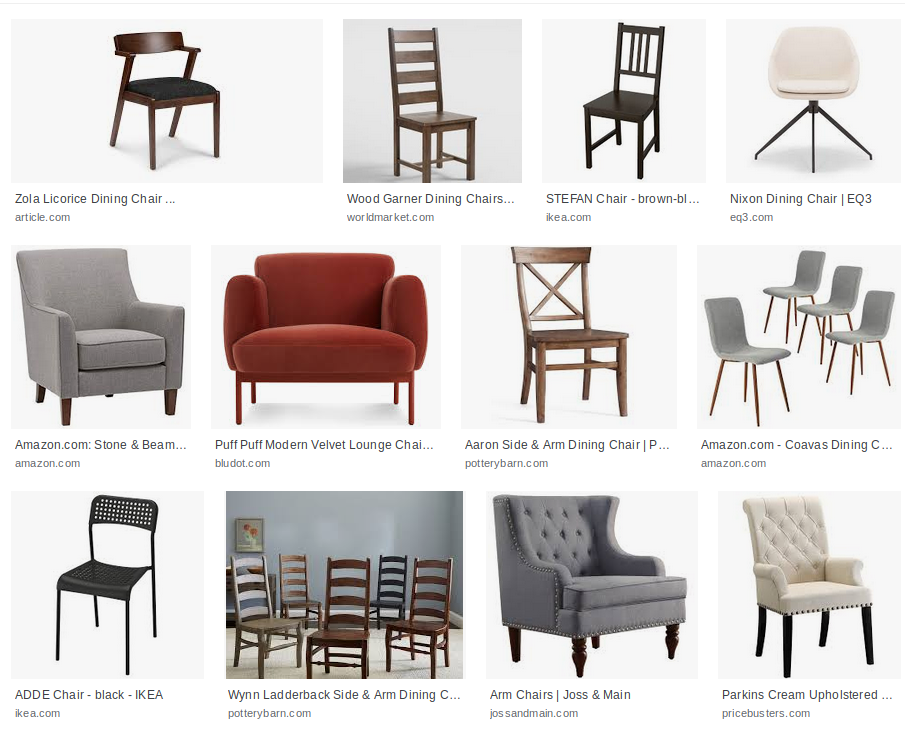

Language has a lot of really complicated concepts: to really understand what even a simple word like “chair” means, and know that a person can sit on a chair but not sit inside a chair, an agent must have a concepts for objects, space and function, which really require a body and sense of self as well. Understanding even basic words becomes very complicated very quickly. It’s no surprise that Google opted to skip over understanding. What if we started with something simpler?

Recognizing Things

Even if our AI can’t understand what a chair is from language, maybe it can learn to see a chair and recognize it. This problem brings us from language to vision, which turns out to be difficult as well. Why is it difficult? Well, computers don’t have eyes, so they use cameras to see the world, and cameras capture images as pixels. Pixels make it easy to reproduce images, but they don’t really say anything about the objects they depict directly. As in the image above, there are lots of things which look very different that all count as chairs — our agent must learn what these objects have in common. Up until a few years ago, algorithms to solve this problem didn’t work very well.

But around 2012-2014, computer vision using deep convolutional neural networks (a particular algorithm, loosely inspired by the human visual system) started doing much better, and seemed to learn to recognize objects extremely well. Instead of relying on a human to comprehensively define what is and isn’t a chair, or outline what features in an image might distinguish chairs from non-chairs, the algorithm only needed a whole lot of images, either labeled as “chair” or “not chair” to learn what distinguished them. While it’s clear that an AI system trained in this way won’t understand what people use chairs for, or why we sit on them and not inside them, I think it’s reasonable to say that it has learned what a chair is.

So what about more complicated concepts? It turns out that these algorithms work well for problems like activity recognition (identifying what someone is doing) and prediction (identifying what someone will do next). They can also classify very abstract concepts like the mood of a painting, or whether a photo is cute or not. So if our algorithm can understand what a chair is, does that mean it can understand cuteness too?

My gut instinct is that our algorithm might be able to learn which things indicate that an image is cute, but not the concept itself. To investigate this idea, I did an experiment.

Cuteness

So, before going into my experiment, we should dig a little into cuteness. Unlike other abstract concepts, there is psychology research on why we find certain things cute. Cute things trigger an instinctive response to infantile features that the psychlogist Konrad Lorenz called Kindchenschema (literally “baby schema”). Humans exhibit a positive affective response when they see cute things, including human children, animals and inanimate objects that display infantile features, and this response is specific enough in the brain to be detected using fMRI, but has remarkable effects on our behavior which can be exploited to achieve societal effects from cartoon marketing to animal conservation.

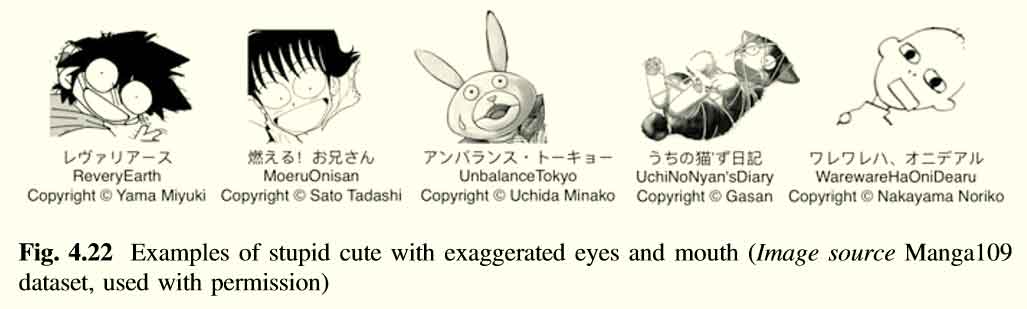

Masaaki Kurosu, Aaron Marcus, Ayako Hashizume and Xiaojuan Ma, a group of human-computer interaction researchers, have a different take on cuteness in their book “Cuteness Engineering: Designing Adorable Products and Services.” They argue that cuteness is a much broader, socially constructed and culturally relative concept which is sometimes related to gender. They enumerate a taxonomy of cuteness, including 24 different reasons something can be cute spanning different kinds of exaggeration, cultural associations and gender-related concepts.

They also claim that cuteness as we understand it today is a relatively recent phenomenon: the word ``cute’’ itself 19th century American slang’s bastardization of the word acute, meaning sharp, and unlike other aesthetic concepts like beauty, cuteness does not have a deep philosophical tradition discussing it. Cuteness already has an influential role in design, though, as interfaces which are designed to be cute are used to calm and persuade us. Cute designs are particularly prevalent in China and Japan, where cuteness engineering has seen extensive corporate attention.

But regardless of where it comes from or how relative it is, cuteness is definitely a concept that we can label in images. So if our labels are consistent, it is reasonable to say that we can teach an algorithm a definition of cuteness (even if it’s not the definition).

Experimenting with Cuteness Detection

So can our algorithm (a deep convolutional neural network) really understand cuteness? To investigate, I trained one of these models. I won’t go into the specifics here, but I use data from the National University of Signapore’s multi-class classification dataset, which has over two hundred thousand images collected from the photo sharing site Flickr, labeled with one thousand tags, one of which is “cute” which we use.

Our model quickly reaches around 79% accuracy, so it definitely is able to distinguish cute images from non-cute images, but what did it actually learn? Well, these models are difficult to interpret — they have millions of parameters and don’t have features like keypoints or bounding boxes for us to investigate. Instead, we can compare this model to other models which are easier to predict, and compare the mistakes they make.

The three models I use for comparison are K nearest neighbors, a Viola-Jones face detector and decision trees. Again, I’m not going to go into the details, but K nearest neighbors compares the image to other images and says “this image is cute if it looks similar to other cute images.” The face detector just detects faces, so it says “this image is cute if it has a face in it.” To contrast, the decision tree doesn’t work with pixels, it works with the other tags in the dataset, and comes up with a series of rules to determine whether an image is cute, which means it says “This image is cute if it has the same objects as other cute images.”

If our neural network makes the same mistakes as the K nearest neighbors model, that means it memorized a few pixel patterns and called those cute. If it makes the same mistakes as the decision tree, that means that it only learned which kinds of objects are cute, not why they look cute. So what did it do?

Results

First off, the nearest neighbor model fails horribly, achieving 50% accuracy, which isn’t better than random guessing. Since our network didn’t fail, it means it isn’t just memorizing cute images. The Viola-Jones face detector ends up around 54% accuracy, which isn’t much better than random guessing, so our model wasn’t looking for faces either.

The decision tree, on the other hand, does as well as the deep model, achieving 79% accuracy. It seems to learn which kinds of objects are cute, rating tags like “pet,” “baby” and “dog” highly. So does that mean our algorithm is just learning which objects are cute?

Not quite. Below are some example outputs where the ground truth, the cnn and the decision tree disagree.

The lunchbox and small basket show that our model is certainly better than the decision tree. The tree asserts that objects like lunchboxes and baskets aren’t cute, but we find them cute because of their size or decoration. The bird crossing the street, the chair and the squirrel are examples where I’d side with my model over the ground truth. Strangely, though, there are also confusing cases like the mountain which are difficult to explain.

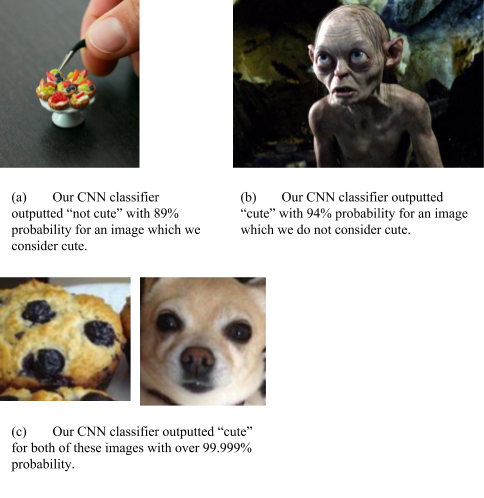

So from these examples, I’d say that the model has a better idea of what cute is than the decision tree, and sometimes than the labels from the dataset. However, we can come up with some more challenging examples:

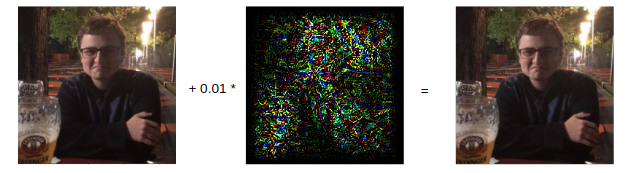

These examples are challenging. We could just call these the model’s subjective judgement and call it a day, but I think these examples are warnings that our algorithm may not have it all figured out. Finally, we can make matters even worse:

On the left is a picture of me. I don’t think it’s a particularly cute picture, and the model agrees. After adding the image in the middle (which is really just a little numerical tweak to each pixel), we get the image on the right. I think it looks the same, but the model disagrees, and thinks it’s extremely cute. Why thank you!

Takeaways

So what does this mean? Well, for starters, my hunch was wrong: a deep neural network does not classify cute things based on whether they look like cute images it has seen before, contain objects which are considered cute, or contain faces. It seems to have a reasonable understanding of cuteness itself, as a visual schema. However, it can still be manipulated in strange ways, so its understanding of cuteness must be different from ours.

Why does this matter? Since we don’t really know what intelligence is or how to detect it, practical-minded intelligent systems researchers settle for anything which creates a believable illusion of intelligence. It turns out that even very simple computer programs can behave intelligently if we limit their range of behaviors and bring humans into the mix. A good example of this phenomenon is the Roomba, a robot vacuum cleaner. The Roomba’s instructions are extremely simple, but humans will ascribe it complex emotional states, and say things like “Oh look, it’s lost!” or “It’s really trying its best!” Of course, a Roomba is following a simple movement algorithm, it doesn’t know where it is and it’s not “trying” to do anything.

If we want our intelligent systems to respond to emotional stimuli like cuteness as a human would, they need to be able to interpret these stimuli believably. That means they shouldn’t be fooled easily by things like muffins or slightly different pixels. If we attempt to make a machine react to these things to make it more relatable, but don’t get it perfectly right, we might fall into an uncanny valley and alienate people instead.

So why don’t we just tune our models and increase accuracy? While that’s a reasonable option for images of chairs, since most humans can identify whether something is a chair or not more than 99% of the time, cuteness, and other abstract or emotional categories require some amount of interpretation, which is subjective and culturally relative. Two humans may only agree on 70% or 80% of our images’ cuteness labels, which is already around where our model is performing!

So why do we think cultural differences between humans are okay while someone finding Gollum or a muffin cute is weird? I don’t really know. We might have an internalized idea of what sort of differences are “allowed” due to culture and opinion, or we might think other cultures’ definitions of cuteness are just as weird as a machine! I think that’d be a good area for future work.

Wrapup

I’m going to leave it there for this post. If you have any ideas for ways I can continue this work, let me know via an email or tweet via the sidebar! I’m still not quite sure where (if anywhere) this project is headed and would appreciate suggestions!