Sonifying the Melodramatic Life of my Roomba

tl;dr I procedurally generated some musical accompaniment for a video taken from the perspective of my roomba! Watch it here:

Randomness in Music

Since finishing my undergrad honors thesis on chorale composition, and by doing a related project with Chris Raphael here at Indiana, I’ve been curious about alternatives to randomness in AI-generated music. Why? Well, random melodies sound boring. More formally, our brains have a special way of processing random things in sound so that we end up ignoring them. This property is most apparent when dealing with audio noise (uncorrelated random samples generate white noise), but I’m beginning to think a similar, less noticible version applies to melody as well.

I don’t have any serious evidence for this claim, but I’ve noticed that when I listen to randomly generated melodies, I ignore them. To some extent, this is happening because they are unfamiliar, performed without any musical expression and totally insignificant to me. But I think there’s another factor as well: when we randomly choose our notes, even if we have a very sophisticated, highly conditional distribution, we still choose notes at random, and our brains are more likely to ignore and forget them as a result. I don’t know if there’s anything fundamental that makes the melodies that we write non-random. It could have to do with mirror neurons or experiencing the manifestation of freedom by the spirit of the composer, but I’m not sure.

These issues got me thinking: what other things could we base musical decisions on other than random chance? John Cage’s music is well known for its reliance on indeterminacy, in the form of chance (e.g. Music of Changes, which is made using a Chinese divination practice), the ambient sound of the performance space (e.g. the famous 4’33”, in which the performer makes no sound, and everyone is stuck meditating on the sounds of a quiet concert hall) or performer choices (e.g. Aria which requires the performer to interpret a graphic score). The concept of interpretation gets to the heart of what I’m thinking about. Instead of simply making choices at random, can a computer come up with music by interpreting something non-musical as music?

Video Sonification

Rather than a graphic score, though, I decided to have my system interpret a digital video. The same principles apply: to interpret something visual, we need a metaphor to map visual parameters into musical parameters. By turning data into sound, we end up in the world of data sonification, which is a really neat area of research related to data visualization. While data sonification research usually tries to communicate the properties of the data through sound in an aesthetically pleasing way without embellishing it too much (so that it could be used to communicate that data as well as a visualization, possibly for the visually impaired), I’m here to make some algorithmic music, so I don’t need to take it as seriously.

In a more developed form, this paradigm for musical composition could be used to generate a film score for your life. It would use a video feed of whatever was in front of your eyes and come up with music to match the tone of your experience. While I don’t know if anyone would want such a thing, it’s a neat concept. We could also imagine a smarter creative agent finding the mapping between video and audio itself, performing the interpretation and compositional process that I went through.

But this was a class project, and I wasn’t able to be so bold. Instead, I had two goals. First, I wanted it to be clear that the audio was based on the video somehow. This challenges the listener to think about how they might be linked, and pay closer attention to both the music and the video than they would have otherwise. Second, I wanted the music to develop as the visuals do. This coupling introduces structure to the music without adopting a specific musical form. It makes the composition process indeterminate without being random, and allows it to inherit whatever form exists in the video.

The video features I ended up using are all based on color clustering and gradient orientation. I use an algorithm called K-means clustering to group the colors in the video into 12 categories, then use the number of pixels assigned to each color cluster as a parameter for different musical qualities. For example, the low note’s frequency is determined by which color bin contains the most pixels. The image below shows the 12 color clusters in the video I ended up using.

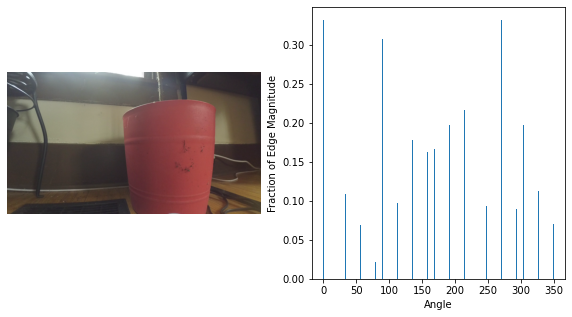

The gradient orientation is based on a feature extraction algorithm called Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG). The idea is that you find the edges in each region of the image, then make a histogram of the directions that those edges point. HOG features are useful in computer vision because they describe objects very well, objects tend to have distinctive combinations of edges. I just use the histogram of gradients over the whole image, and use the most frequent histogram bin to determine the pitch of the pluck bass note.

Roomba-Centric Video

So what video do I sonify? I experimented with a couple different options, including a video of my apartment, and some videos from walking outside. I eventually settled on a video I recorded by taping a camera to the top of my roomba. If you’re unaware, a roomba is a small robotic vacuum cleaner which moves randomly around a room, turning whenever it hits something. While it doesn’t use a very sophisticated algorithm to navigate, it works better than you’d expect for covering all of the floor space in a room. Of course, it tends to vacuum the same area over and over again until it escapes, and often bumps into the same object repeatedly to find its way around. There’s actually some interesting theory behind the Roomba’s algorithm, its creator, Rodney Brooks, became pretty well-known for his ideas about intelligence and representation.

This idea might seem strange at first, but there is a lot of drama in the life of a roomba. There’s just something funny and sad about watching a robot move slowly towards a wall. You know it’s going to hit the wall and that there’s nothing you can do to stop it, but you still pity the roomba when it does collide. And, because the camera is attached, you feel the shudder when it hits and share the roomba’s pain. Over the course of the video, eventually the roomba escapes into the bedroom after being stuck running into the same objects for the past 8 minutes and it’s a triumphant moment. It eventually gets stuck in some clothes and spends the last minute spinning in a circle; the tragic end of a hero’s journey across my apartment.

The video is 15 minutes long. Watching the whole thing is like listening to several minutes of Erik Satie’s Vexations: it slowly drives you mad, but I quite like it. If you’re short on time, though, I won’t judge. I most enjoy 8:30 through 10:30.