The Problem With Beauty Equations

Over the past few months, I’ve been digging into a strange subfield of computer vision called “image aesthetic quality assessment.” In this subfield, researchers study algorithms for curating photographs based on aesthetic quality, separating out poor photos from good ones. To some extent these algorithms work: they report over 90% accuracy when classifying between low and high quality photos in a benchmark dataset.

I’ve become absolutely infatuated with this research topic, not because I think that what they are doing is good or right, but because I think their work is a really good way to approach a difficult issue at the core of all the topics I study. It’s really difficult to just talk (or write) about philosophy, so I’d like to show you by looking at a couple of examples.

This blog post is based on a short paper I’m presenting this week at ICCC, which is in turn based on a paper I wrote for my qualifying exams. In them, I investigate the concept of the “aesthetic gap”: the difference between information that you can get from the pixels of an image and information related to the feelings that that image might evoke in a human. Particularly, have computer vision algorithms crossed that gap? Can really sophisticated machine learning models actually reason about the way images make people feel?

Is this beauty?

Aesthetics Before Computer Vision

In philosophy, aesthetics is the study of beauty, taste, experience and judgment. These are dense topics of study plagued with questions, many of which have been debated by philosophers since Plato. One of these questions has to do with beauty and where it exists: is beauty something which exists in a work of art itself, or is it something which exists in the mind of a person looking at the art? If it’s in the work of art, then why do people disagree about it? If it’s in the mind, then why do many people have the same experience?

Lots of people have weighed in on these sorts of questions (Immanuel Kant has a pretty important take on it) and I’m not going to get into the details here. What we should note, though, is that taste is subjective: it does vary from person to person.

Despite this fact, lots of people through history have tried to quantify and measure beauty. These attempts range from “rules of thumb” which make suggestions for artists (like the ancient architect Vitruvius’ principle that temples should use ratios taken from the ratios in the human body), to “beauty equations” which attempt to reduce beauty and judgment to a calculation. I have two interesting examples of the latter:

- Fechner The 19th century psychologist Gustav Fechner found that when presented with rectangles, people preferred the rectangles with ratios between their sides equal to the golden ratio (\(\phi = \frac{1 + \sqrt{5}}{2}\)). Fechner’s finding spiraled off into a whole mythos about the golden ratio involving the Parthenon, paintings of Leonardo da Vinci and the writing of Virgil. These relationships are myths, however. This paper by George Markowski explains it better than I could.

- Birkhoff In his 1933 book Aesthetic Measure the mathematician George Birkhoff puts forward a theory of aesthetic experience which reduces to an equation. He claims that in any medium, given a measure of order \(O\) and a measure of complexity \(C\), beauty can be measured by a value \(M = \frac{O}{C}\). This equation can be a little puzzling at first, but Birkhoff thinks of order in terms of scale and scope (how much content is there?), and complexity in terms of information theory (how difficult is it to describe the work?).

These approaches to quantifying aesthetics have not been well-received by philosophers. I’ve got some more specific quotes in my paper, but the takeaway is that philosophers who study aesthetics believe that reducing judgment to a numerical measurement is a fool’s errand.

They also don’t work. Research has shown for various different kinds of aesthetic measures that simple equations just don’t do a very good job at predicting how humans feel. This fact should be obvious because if these historical approaches had found a perfect beauty equation, we wouldn’t be arguing about it today. So clearly, simple equations are insufficient for crossing the aesthetic gap. But what about more sophisticated equations learned from data?

Image Aesthetic Quality Assessment

Work in this space in computer vision began in 2006. Some researchers were interested in a computational aesthetics goal, inspired by Birkhoff and Fechner. These researchers were interested in finding characteristics which make some images more beautiful than others. A second group of researchers saw aesthetic quality assessment as the natural extension of an existing field: image quality assessment. Image quality assessment is the study of metrics for things like blur and image degradation, and has been studied by scientists and engineers for a long time. This second group of researchers believed that the next step beyond measuring blur was predicting whether a photo had been taken by a professional or amateur.

As time went on, however, these two goals merged: researchers both started equating “professional quality” with “high aesthetic quality” and relying heavily on large datasets to define what exactly they meant by “professional/high quality” or “amaetur/low quality”.

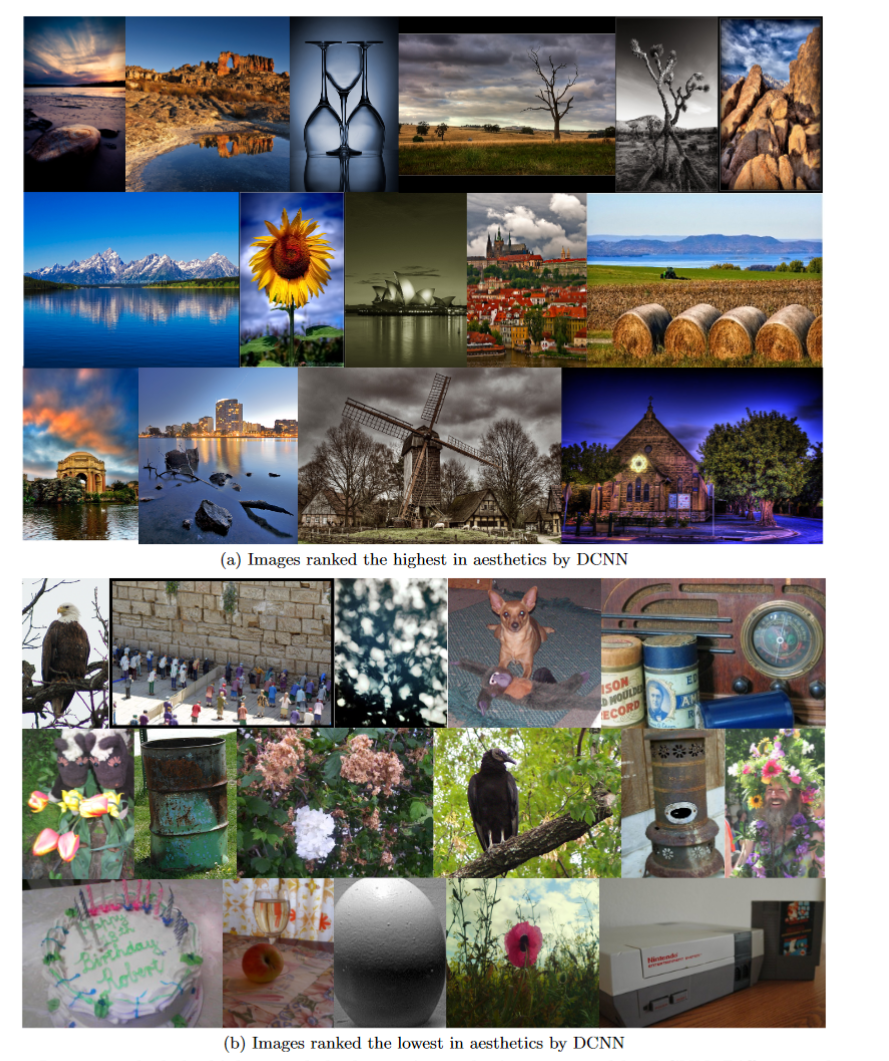

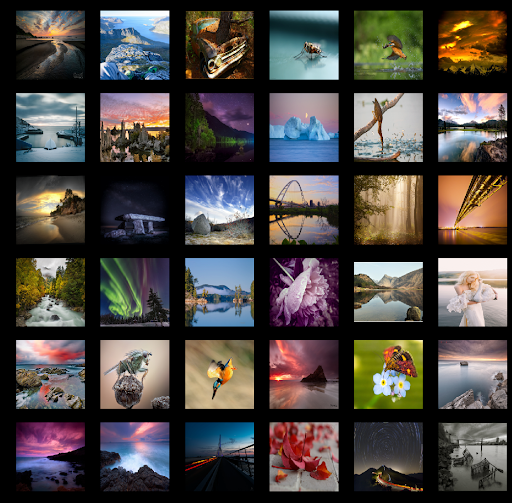

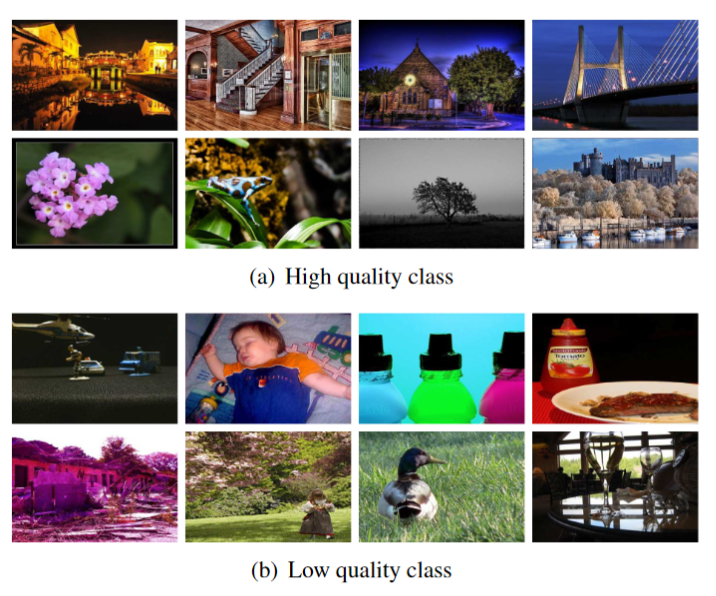

Here are two examples of figures from IAQA papers comparing high and low quality images (Lee et al. 2019 and Lu et al. 2014, respectively).

I’d push back a little bit on relying too heavily on data. While all the images in the “high quality” class are certainly beautiful, they are not representative of all the ways that an image can be beautiful. They all share a similar style, relying on dramatic colors and impressive content, usually from nature. There are, however, many ways for photographs to be beautiful, and it would be inappropriate to use such a style in some genres of photography (like candid or news photography).

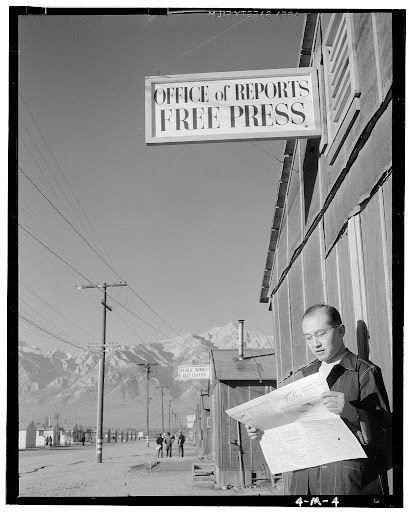

For example, this photo, “Roy Takeno reading paper in front of office” by Ansel Adams was taken in a Japanese internment camp in 1943. It is a beautiful photo, but it does not have nearly as dramatic a composition as the “high aesthetic quality” photos, and gets an aesthetic score of 58% when I run an IAQA model on it. I find it compelling, though, because of its juxtaposition of symbols: can there really be a free press in internment, for example? But no computer vision model working without context could ever know that.

In other words, the IAQA datasets tend to conflate the potential to arouse emotions (the thing we’re interested in) with really explicit emotionality (which is easy to measure from pixels). While measuring explicit emotionality is a fantastic research result, IAQA models are still beauty equations which still don’t cross the aesthetic gap.

The Aesthetic Gap

So what hope remains for modeling aesthetics? It should be clear by this point that the answer isn’t “find a more sophisticated beauty equation and more training data.”

One possible answer is that there just isn’t an aesthetic gap: whether we like an image or not is a gut reaction, and any explanations that we come up with actually are post-hoc justifications for our reaction. This interpretation is supported by results from neuroaesthetics which show that judgment is actually a pretty low-level operation in the brain.

Another answer is that the gap is still out there and we haven’t crossed it. To cross it we might need a model which takes more information about context and meaning into account, which is certainly possible, though difficult.

I would argue, though, that there’s a big question left over. Even if we had a perfect aesthetics model, if you and I disagree about the beauty of a work, who gets to be “right”? Me? You? An average/majority opinion? Or is the computer itself an agent who gets to experience art and have its own judgment? In other words, when a computer vision algorithm solves a subjective problem, who is the subject?

This is a really important problem that extends to a lot of different problems across machine learning. I’m still exploring it, and I will probably write another blog post about it in detail at some point. The short answer, though, is that I think the model needs to be personalized: instead of making a judgment of whether an image is beautiful, it should predict how one specific person will feel about that image. That sort of prediction problem is well-defined and solvable. If we want an aesthetics assessment model which works for multiple people, it should be personalized to each one, and avoid defining one perspective (like the average) as normal.

Thank you for reading this far! Here’s the link to my conference paper based on this work. Please let me know if you have any questions/comments!