Tracing the Origins of Optimizationism

In mathematics, optimization is a technique for finding the highest or lowest value of a function. In machine learning we use optimization as a tool for fitting models to data, but it is more than that. In many ways, computer scientists engage with optimization more like an ideology.

Let me show you what I mean through some examples. In the same way that we define constraints and adjust parameters to minimize loss functions within those constraints:

- We choose our models and algorithms to optimize on performance metrics.

- When programming, we choose our tools to minimize expected programming time + running time.

- When teaching, we assume our students are operating in the same manner: trying to minimize the amount of work they have to do to get a good grade.

- When writing, we tweak our papers to maximize our chances of getting accepted to conferences and journals, subject to page length constraints.

- At those conferences, researchers attempt to maximize both their paper’s odds of getting used and cited, and their own odds of getting hired.

Even anecdotally in life, the same kind of thinking emerges:

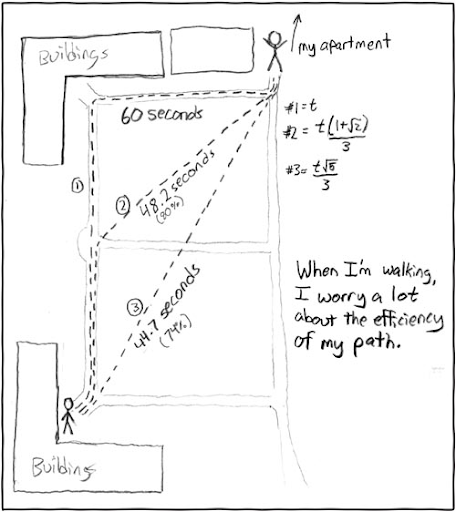

- Which paths from building to building on campus minimize travel time subject to the constraints imposed by walls, trees and the awkwardness of walking off paths?

- Which foods maximize healthy eating per dollar?

- Which dental plan is cheapest and easiest to use while still covering wisdom tooth removal?

- Which speed should we watch YouTube videos at for maximum enjoyable content consumption per hour?

For lack of a better term, I’m going to call this ideology optimizationism. By using the suffix -ism, I don’t mean to say that this is a political, philosophical or religious position as much as it is a way of seeing the world and a guide to action in everyday life.

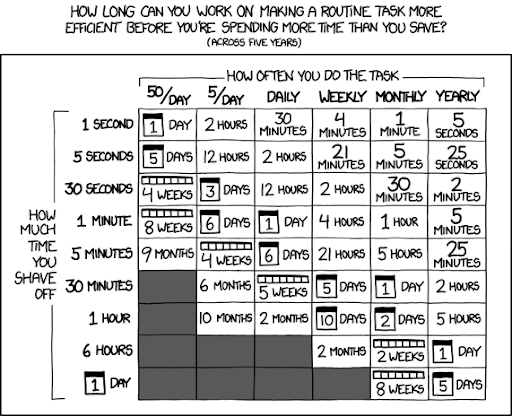

The webcomic XKCD has a ton of examples of optimizationism, since it’s kind of ridiculous when you think about it.

When used in the real world, optimization becomes less a way to solve mathematical problems, and more a guiding principle to make sense of the complexity of everyday life. Rather than deal with difficult tradeoffs and decisions, in any situation we simply pick some characteristic, optimize for it and consider that choice to be the best one. There’s a practical benefit too: if someone questions our choice, we can point to its optimality and claim that we made the decision for a nice, objective reason.

But ultimately, while “optimal” literally comes from the Latin for “best,” there’s nothing inherently best in the real world about being optimal according to a metric: most things we’d like to optimize for (like the quality of a model, or the healthyness of food) can’t be measured directly since they’re ultimately subjective and contextual.

Where did optimizationism come from? Why is it so prevalent in computer science? And is there a version of computer science without it?

In some ways, optimizationism is a defining element of computer science culture. Our tendency to measure performance and search for improvements has made us the darling discipline of neoliberal university administrators, who seek to measure performance in research and teaching, eliminate inefficiencies and maximize productivity through competition.

Unfortunately, that tendency has also created some amount of bad blood with those in the humanities, who oppose the neoliberal turn, and find attempts to measure and optimize their work to be reductive and insulting.

Over the past three years, I’ve been studying some of the barriers to collaboration between computer science and the humanities, which has led me to ask a lot of questions about this way of thinking. While it resembles neoliberalism, optimizationism has a different character and feels different. If that’s true, where did optimizationism come from? Why is it so prevalent in computer science? And is there a version of computer science without it? I’d like to attempt to address those questions in this post by exploring the history of optimization.

By questioning optimizationism, I am not arguing that algorithms which find optimal solutions are bad, that the mathematics of optimization is somehow incorrect, or that there is something wrong with using optimization in our research. Optimization is mathematically correct beyond any doubt, and a brilliant innovation, but correctness or beauty does not mean that we can approach something uncritically or ahistorically. Instead, I claim that optimizationism is not an essential part of computer science, and we should try to imagine new ways of being computer scientists without this ideology.

Origins of Optimization

Mathematicians have been solving problems involving minimization and maximization since antiquity. For example, Euclid, the “father of Geometry” famously proves that, given a fixed perimeter length, the rectangle with maximum area is a square. Here,

- the “target” or “dependent” variable is the area

- the “independent” variables are the side lengths

- the problem is subject to a constraint: that the side lengths add up to a specific total perimeter.

The solution ends up being beautiful: rather than have some strange number as the ratio between the length and width, the optimal ratio is 1. Euclid managed to prove this fact without many mathematical tools we take for granted, like algebra or fractions.

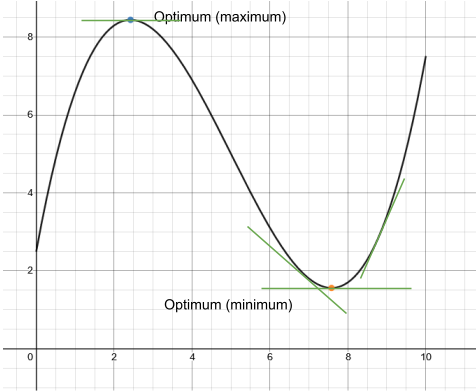

While there are some other examples of early approaches for optimization, general methods for solving optimization problems were not invented until Isaac Newton and Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz simultaneously developed calculus in the 17th century as a language to talk about the motion of the planets. Calculus is all about measuring the steepness of curves (the “derivative”), and at the highest or lowest point, the curve changes from going up to going down (the derivative goes from positive to negative, or vice versa), which makes calculus very useful for finding optima. In the plot above, the light blue point is the maximum and the orange point is the minimum. At both points, the derivative (the slope of the tangent line, in green) is 0, while at other points, the derivative is either positive or negative.

In the early 19th century, Adrien-Marie Legendre and Johann Carl Friedrich Gauss simultaneously arrived at the idea to find optimal guesses for uncertain numbers. For example, we can find the position of a planet under error-prone measurements by optimizing that guess to minimize the squared differences between its predictions and the actual values (the “method of least squares’’). In this framework, the target is a measure of error, and the independent variable is the estimate.

At this stage in the story, we have most of the pieces of optimization which are used in computer science today, but it isn’t functioning like an ideology yet. Gauss, for example, made use of optimization to analyze the motion of the planets and even complete a horribly inaccurate land survey of Hanover, but he didn’t use it to study society or make personal decisions. I’m not a historian, and I haven’t researched this fully enough to know for sure, but I can’t find any references to the sort of optimizing thinking computer scientists do today.

Using Optimization to Measure Society

The idea of using optimization together with probability theory to come up with estimates (the method Ronald Fisher would later name “maximum likelihood estimation”) gained popularity during the latter half of the 19th century, especially for estimating average characteristics of people, like birth, death, marriage, crime and poverty rates, as well as their social causes. These lines of inquiry led to the intertwined development of sociology, statistics and eugenics. For example, the early statistician Karl Pearson developed his famous correlation coefficient to understand the inherited aspects of social character, like intelligence, and developed methods for optimizing human populations.

Pearson’s perspective, which was shared by many 19th century scholars, was influenced by Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution. Darwin famously claimed that mutation created natural variation in populations of organisms, but only the organisms which were best fit to their environment would survive to reproduce. The process of selection is an optimizing force: more optimally fit species will outcompete less fit ones.

The early sociologist and statistician Francis Galton had the idea that human abilities were subject to the same laws, which was further developed in Herbert Spencer’s social Darwinism: that humans were competing with one another for Earth’s limited resources, and more fit humans were destined to outcompete less fit humans, so nations should improve the fitness of their populations (funnily enough, this is the origin of the term “fitness” as a synonym for “exercise”). Of course, 20th century Fascists gleefully took this idea to its extreme and decided to create industrial systems for murdering millions of people they deemed unfit or degenerate in some way.

The thinking of Pearson, Galton, Spencer and other early statisticians and social scientists is an example of how optimization transforms from mathematical method to ideology. The concept of optimality is abstracted, and allowed to extend into reality, where actions, policies and even people can be described in terms of their relative optimality. While the mathematics of optimization are undeniably correct, the application of such ideas to reality is not. Humans and our actions are not mathematical functions, they have no parameters and cannot be computed or evaluated inherently. Connecting optimization to society requires making measurements and judgments, and they have assumptions which cannot be made neutrally and have thus been questioned by generations of sociologists since.

Optimization in Computer Science

(source)

(source)

In the 20th century, optimization found yet more uses, in operations research, management science, routing and search. New frameworks like George Dantzig’s simplex method for solving linear programming problems and Richard Bellman’s dynamic programming (there’s a really interesting story behind that name) allowed the development of algorithms for optimizing in situations where the earlier calculus-based methods would not apply. A wide variety of decisions could now be made optimally, and scientific approaches to business, government and war became the norm. In parallel, the related mathematics of dynamical systems gave rise to cybernetics: the theory of feedback and control. Optimization procedures and dynamical systems thus became central pillars of modernity, allowing humans to manage highly complex machines and processes.

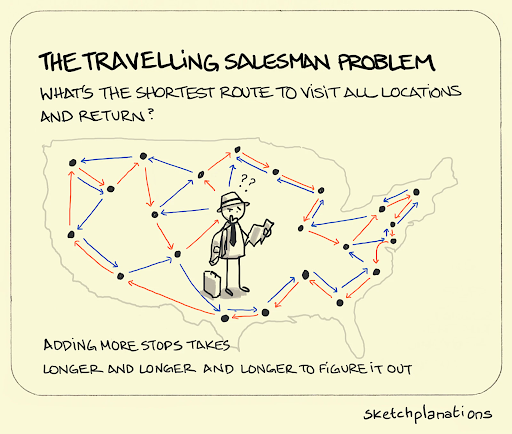

As computers became prevalent, optimization became the basis for a wide range of more sophisticated algorithms for real world problems ranging from transportation networks to factory workload balancing. Through the 20th century, early computer scientists were very optimistic about using optimization as the engine behind artificial intelligence which could make all sorts of decisions. For example, the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP), which asks a computer to choose the optimal order to visit some number of cities to minimize the total distance traveled. While the TSP sounds more like a brainteaser than a serious problem, many real-world problems are quite similar.

Unfortunately, that agenda came crashing back to earth in the early 1970’s due to the work of Richard Karp, who showed that a wide range of combinatorial optimization problems were actually equivalently difficult, and that there were no known efficient algorithms to solve any of them. This observation meant that it was unlikely that anyone would ever develop algorithms which could make complex decisions on any interesting combinatorial problems within a reasonable amount of time. While continuous optimization has seen a surge of research interest from machine learning over the past decades, the dream of fast, optimal solutions to decision problems hasn’t happened.

We see in the development of computer science that optimizationism is more a product of historical circumstances than anything else. Computer scientists study the mathematics and implementation of algorithms and data structures, they don’t study society, management or decision-making directly. But one of the main applications of computers was precisely in making optimal real-world decisions. Over time, it makes perfect sense that computer scientists would start to see decisions in their own lives in terms of the same optimization problems in their work.

Optimization and Neoliberalism

During the 1880’s, at the same time that statisticians were developing theories of eugenics, optimization also found a following in economics. Economists of this era embraced the idea that marginal utility (the value you get from buying one more of something) was the explaining factor behind the prices of goods, and that prices corresponded to the optimal value of a function relating supply and demand. From these theoretical origins came the idea that the free market, like nature, is a naturally optimizing force: companies and individuals behave like rational actors looking to improve their marginal utility, which means they are under pressure to optimize their choices.

In the century since, the relationship between the free market and optimization has found its way into many different parts of our society. In the 1980’s, politicians embraced the idea that free markets, competition and consumer choice were natural avenues to optimize inefficient parts of our society. Unions were defeated and industries were deregulated and defunded, from education to medicine, to encourage competition. While the definition of neoliberalism is debated, there is some consensus that it describes the positions of both major American political parties over the last forty years, and dominates our political conversation. With it, our culture has embraced a renewed focus on measuring desirable qualities and using a system of privatization and incentives to optimize around them.

The neoliberal approach to optimization seems quite different from 19th century eugenics, but it inherits many of the same ideas. For example, consider the No Child Left Behind Act of 2002. This legislation linked federal education funding to a series of requirements based around standardized test results. Schools were required to increase the number of students who met a proficiency standard based on test results, and schools that did not make a minimum amount of annual progress towards that goal could be shut down. The idea that educational systems should contribute to the “betterment” of humanity has its roots in the 19th century eugenics goals of optimizing national populations, the idea that intelligence and education can be objectively measured comes from the same roots and the selection of disciplines like math and reading comprehension for testing (rather than the arts or social studies) actually has its origins in Herbert Spencer’s educational theories, which emphasize a hierarchy of the disciplines, with “functional” disciplines like math and science at the top and “leisure” disciplines like art and music at the bottom.

To make matters worse, there are reasons to believe that such approaches to optimizing education do not work. In the 1970’s, Charles Goodhart, a British economist and expert on monetary policy, made the observation that “Any observed statistical regularity will tend to collapse once pressure is placed upon it for control purposes.” In other words, when we notice a pattern relating some difficult-to-describe phenomenon (like “quality of education”) to some metric (like standardized test scores), optimizing with that metric as a target (like punishing schools which do not improve their scores) means it will cease to be a useful metric (schools will teach students how to take tests rather than give them a quality education).

Goodhart’s law is particularly damning for optimizationism because it assumes that the optimal solution is the best one, since it has the highest or lowest possible value for a metric (e.g. the highest accuracy model is the best one). But paradoxically, if that metric originally was based on a statistical regularity (e.g. accuracy on a finite test set), then it ceases to be a good measure. Instead, we need to turn to other approaches to evaluate the quality, or our solution will become brittle and sacrifice other desirable aspects to improve the one we measure (e.g. overfitting on the finite test set).

Goodhart’s law is not a flaw of mathematical optimization (we even have regularization methods to prevent it) or even a new idea in computer science (Don Knuth famously said “premature optimization is the root of all evil”); it only arises when we assume the optimal solution is the best one in the real world, without considering other, less measurable factors.

In short, the trend towards optimization in education and optimization in computer science are linked. The same 19th century ideas about optimizing human populations developed the statistical tools at the heart of machine learning as well as the idea that competition between disciplines could be used as a force to improve education, much to the detriment of the arts and humanities. While optimizationism in computer science at times resembles neoliberalism, it is more an ideological cousin than a child or sibling.

Moving Past Optimization

My ultimate interest is in breaking down these barriers and finding room in computer science for collaboration with artists and humanists. For better or worse, that involves subverting optimizationism. But what would a computer science culture less focused on optimality look like?

Unfortunately, it is notoriously difficult to imagine significant cultural change in one’s own field. When we introduce students to computational complexity theory, we teach them that more efficient algorithms are better. Similarly, when we introduce students to machine learning, we teach them to think of learning as optimization, where the model which is most optimized has learned the most. While these ideas are extremely helpful for understanding computer science and writing good code, they limit our ability to think about alternatives.

I don’t know exactly what a less optimized computer science would look like, but we have a unique opportunity to move away from neoliberal competition between academic and corporate labs by exploring alternatives to optimizationism.

To illustrate the kind of path forward I’m imagining, consider these artistic examples:

-

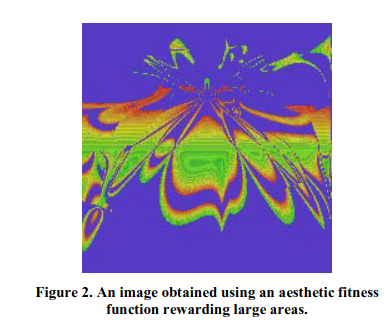

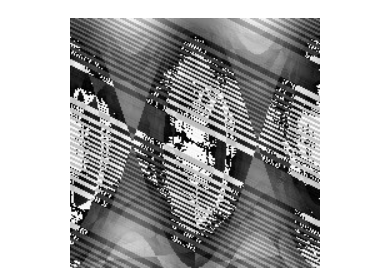

Gary Greenfield’s Computational Aesthetics

Gary Greenfield’s computational aesthetics: two examples of art based on optimizing on a measure of aesthetics based on large regions (left) and entropy (right). (source)

In the mid 2000’s, computer graphics researchers, including Gary Greenfield, developed computational aesthetics. A branch of evolutionary computing, computational aesthetics uses genetic algorithms to optimize art, with some aesthetic measure as a fitness function. Genetic algorithms are an evolution-inspired optimization strategy which simulates selection and mutation to search a discrete or continuous parameter space for more optimal values. -

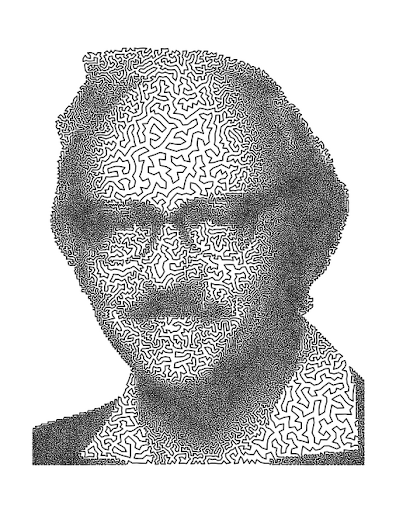

Bob Bosch’s Traveling Salesman Problem Art

Bob Bosch, George Dantzig (left) and Outside Ring (right) (source)

Bosch’s art takes optimization and flips it on its head. Instead of optimizing for some real-world problem, or optimizing on an aesthetic measure, he fabricates collections of cities for the Traveling Salesman Problem, and approximately solves them using heuristic-based methods, so that the path of the solution is visually interesting.

If we contrast these two approaches to optimized art, we see a way to transition away from optimizationism. In Greenfield’s work, optimality is treated as a goal: any images which are much less optimal (according to his aesthetic measure) are culled at each selection stage of his algorithm, so only the highest scoring images are shown. In Bosch’s work, however, optimality is less a goal and more a texture, so optimality exists as a means to an unmeasured artistic goal, rather than a measurement of that goal. This isn’t to say that Bosch’s art is better than Greenfield’s. I personally quite like them both.

I think, as computer scientists, we can take inspiration from that and move past optimizationism as a discipline. Instead of valuing optimality itself, and using optimization as an organizing principle for our work and our lives, we can merely use it as a tool and appreciate its inherent beauty and brilliance. While there are other points of tension between computer science and the humanities (automation and surveillance come to mind), I think addressing optimizationism would really help.