I Read 17 Old Web Design Books and You Will Not Believe What They Said!

Well, you might believe it. They mostly just gave advice on how to design websites. But the thing which I found absolutely fascinating in these books is the way they gave that advice. In fact, we found this style of writing so interesting, we wrote a paper about it, which is now available.

But before I go into that, I want to explain how I ended up reading 17 old web design books. In the summer of 2020, my advisors and I conducted a series of interviews with experienced web designers as part of our investigation into the history of web design. One of our participants graciously went through her bookshelf and talked about all of the old books she used to learn design principles.

We noticed as we analyzed our results that our other participants were often mentioning books as well. Why? Well, in the words of one participant “We don’t really do books anymore. But back in the day that was the only thing. We, I mean, there was stuff online, but it was really all about books.” As the web was growing, people couldn’t learn web design from websites or classes like they do today, they mostly learned them from books.

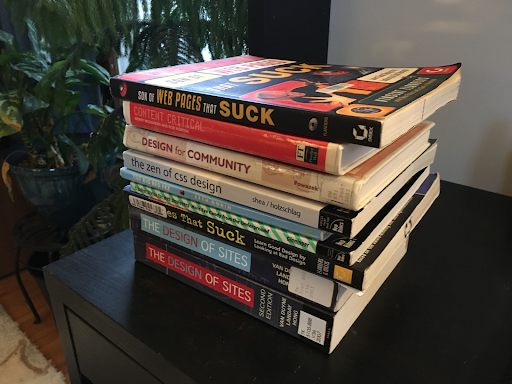

Anyway, I spent the fall and winter of 2020 tracking down and reading as many of these old web design books as I could. As a result, this is what my desk looked like for most of these months:

So what exactly is the style of writing used in dot-com era web design books? We found five trends:

-

Justifications from personal credibility: The authors of these books don’t really give evidence for their recommendations. Instead, they start by showing us that they really “get” web design and deserve our trust, and then they simply tell us how to design websites well. But they don’t justify their credibility just using a resume – they also prove to us that culturally, they’re the right kind of person to be good at designing websites. For example, at the start of The Art and Science of Web Design, Jeffrey Veen writes,

My past is one shared by almost everyone with whom I consider a peer: early video games in elementary school, a Commodore 64 in junior high, and a Macintosh in college. I bring this up because there was a sensation I felt the first time I used a Mac in the dark basement lab at my alma matter. It was a feeling of being disconnected and empowered at the same time…I have spent the last five years of my life making Web sites for HotWired, one of the first commercial publishers to focus its efforts exclusively online. These sites have relied on basic industry standards, have been funded through advertising, and have served a broad spectrum of technically literate users.

Think about that: he not just learned how to code, but he had a specific 1980-90’s upbringing which prepared him for computing. Then, he had a realization in a dark basement lab and worked for a publisher serving technically literate users.

-

Use of humor: Several of these web design books try to be funny. They include visual gags, one-liners and cultural references which have nothing to do with web design, but work well to hold our attention. For example, this passage from Vincent Flanders’ Web Pages that Suck:

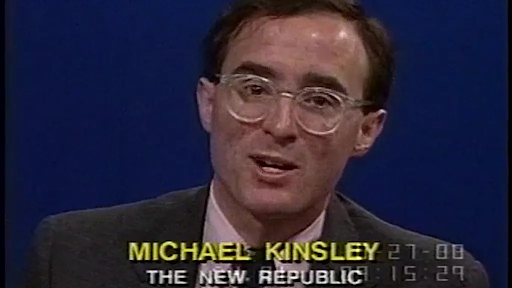

I realize pornography is a touchy subject (pardon the pun) for many people, but we need to look at it in a cool, rational manner because, like it or not, pornography is the kind of content people will crawl through sewers and beg to buy…Like it or not, pornography is the ultimate easy sell because it’s something people will pay to see. They might not pay to read Michael Kinsley’s Slate magazine, but they might pay to see him naked. Well, maybe that’s a bad example. You know what I mean.

Flanders is making the point that web content should be something that people really want. But rather than just say that, he connects it to pornography and makes a joke about Michael Kinsley, the pundit and founding editor of Slate. That last sentence is really interesting because it’s printed in a book. If Flanders really thought that his example was bad, he would have deleted it. Instead, the phrase “maybe that’s a bad example” is part of the rhetorical style.

- Dramatic headings and confident claims: These web design books use ridiculous claims in their sections headers. Things like “Everything You Know About the Web is Wrong” or “Digital Metaphor is the Enemy of Progress!” These kinds of headings read like clickbait, which is strange to see in a book, since we presumably have already bought the book in order to read the section headings.

- Rhetorical use of the past and future: The books generally include a summary of the history of the web somewhere in their first chapter. These histories are usually very simplified and present the author’s view of the web as the natural result of history.

- Use of dichotomies to define web design: The books tend to define web design in opposition to other things, usually either art (like, web design is not art, it’s serious business) or engineering (like, web design is not about solving boring technical problems, it’s really about communication).

So why in the world are authors writing about the web this way? We think there are two related explanations:

- Orality: These books are not written as books. They are really more like transcriptions of tech conference talks given by the authors, and serve as advertisements for those talks, and souvenirs for audience-members who enjoy them. While the style these authors use is unusual for written rhetoric, it makes perfect sense in oral rhetoric.

- Nerd Masculinity: These books come from a specific cultural context: Silicon Valley in the dot-com boom. That culture places a lot of emphasis on technical self-confidence, nerd identity and a desire to be the “go to guy” who can “get the job done” (in the words of Marianne Cooper, who did a fantastic study of fatherhood in early-2000s Silicon Valley). These authors wrote this way in order to prove their “culture fit,” which makes them credible and trustworthy.

Implicitly, by writing this way, these authors are taking part in the construction of what it means to be a web designer, who gets to claim that role and how web design relates to other disciplines like art, design, software engineering and marketing. For better or worse, we are living with the consequences of that culture today.

Anyway, if these topics interest you, you should read our paper! We have a lot of analysis and connections to theory (including translational HCI, secondary orality and hegemonic masculinity) that doesn’t quite fit in a blog post like this and some recommendations for how we should teach new design disciplines in the future.