Situated Cameras, Situated Knowledges

Recent crises regarding bias and injustice in AI raise serious questions about our research methods. How should we change our methods to prevent these issues in the future? In this post, I propose an idea for this problem in the context of egocentric computer vision.

Earlier this year, I shared a draft blog post I had written with my advisor. The post was about “egocentric” computer vision, a research area which studies algorithms for analyzing photographs and videos taken from head-mounted cameras. My interest was in the parallel between egocentric computer vision and the concept of situated knowledge from feminist theory.

My advisor liked the post, and wanted to share it with his peers, so I rewrote it like a position paper and he presented it at the egocentric vision workshop at CVPR. It is now available on arXiv. Here’s a revised version of the “bloggy” version.

Egocentric Vision…

Egocentric computer vision is the study of algorithms and models for working with egocentric images – images photographed with a head-mounted camera. That head can be a human head, robot head or even a self-driving car.

Egocentric images are messy: they’re blurry, include lots of hands and objects, and never show the whole scene. That messiness makes for lots of interesting engineering problems, and a wide variety of applications to everything from developmental psychology to robotics.

I’d argue that these images are more objective than clean, well-composed photographs. When a photographer takes a photo, they choose how they want the contents of the photo to be depicted. While an egocentric photo is not unauthored or unbiased, it makes the photographer an explicit part of the scene it depicts, and leaves elements like composition and lighting to chance.

…and Feminist Theory?

Computer vision is in an ongoing crisis regarding bias and injustice. Computer vision algorithms which are sold to the public as objective and neutral recognize black people as apes, attempt to classify sexual orientation based on facial features and generate far more men than women in historically masculine jobs, even when those jobs are close to gender balanced today. I think these incidents are catastrophic failures of our research methods, and demand that we think: how do we know how well an algorithm works?

There are a lot of interesting parallels between this situation, egocentric vision and a key work of feminist theory, Donna Haraway’s 1988 essay “Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective.”

In it, Haraway discusses scientific objectivity and its fraught relationship with feminism. Many of the central questions of feminist theory involve questioning scientific “facts” – particularly those about women and their “natural” role in society. Some feminists cite these conflicts as justification to throw out scientific inquiry itself as biased, but Haraway disagrees. She seeks a way of thinking about knowledge which admits both real scientific facts about the world as well as arguments against sexism inherent in science.

Haraway’s solution is to use vision as a metaphor. She observes that science, when it separates a “view” of the world from the way that it was captured, performs a “god trick” – pretending that an observer’s limited view can actually see everything from an omniscient god’s-eye view. But all vision – human, animal or machine – is actually situated, limited and partial.

In other words, we can’t see things like stars or atoms directly, we can only see them through telescopes or particle collider experiments. When we forget that, and accept scientific knowledge as objectively true without considering the limitations of its methods, we can allow biased results to become “objective facts.” This doesn’t mean that scientific knowledge is totally interchangeable with unscientific knowledge, just that we should consider them both in the context of their evidence and their perspective.

God Tricks in Computer Vision

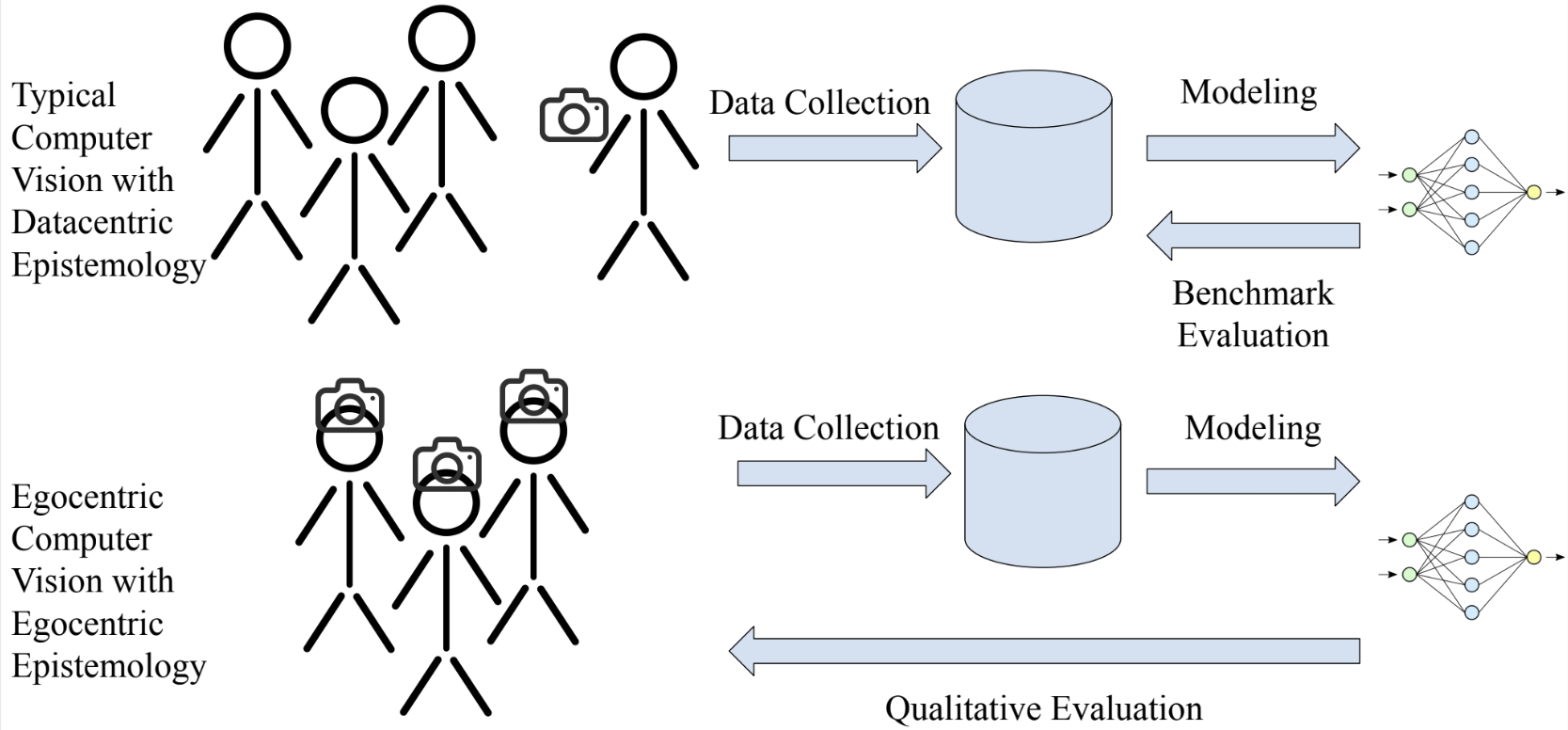

Traditional computer vision takes part in two such “god tricks.”

- It separates cameras from the photographers who take them, and treats them as objective views of a scene.

- It separates datasets from the researchers who assemble them, and treats evaluation metrics computed using them as objective evaluations of algorithms.

Egocentric data avoids the first god trick by placing the photographer in the scene. These images are more like the way we actually see. And importantly, they do not allow the photographer to impose their own understanding onto the image, like in a composed photograph.

But avoiding the second god trick is more difficult. Data for these computer vision problems comes from people, typically crowd workers paid to wear a camera while doing household activities. Then, videos are whisked away and labeled by a different set of crowd workers according to a labeling scheme. Algorithms are trained and performance is measured based on accuracy (or, more often, average precision) with the labels.

Datasets and metrics are designed by researchers because they have a real-world problem they would like to solve. Usually, they do their best to describe the problem abstractly, but there is no abstract way of formulating the task “action recognition,” for example, without assuming something about what an action is. The well known EpicKitchens dataset, for example, defines “action” in terms of English nouns and verbs which participants use to describe their activities. While their use of the participants’ own words is a step in the right direction, it is unclear whether the participants consider actions to correspond directly to noun-independent verbs, whether “turning on the faucet” and “turning on the light” are the same action, for example.

These kinds of biases are not a bad thing! They make the algorithms that we develop useful to a specific real world problem, which gives them value. A totally netural problem statement (if it existed) would be totally disconnected from reality. So, whose perspective should we center when deciding which algorithm performs best for a given problem?

A Proposal: Egocentric Evaluation

Since we are doing egocentric vision, we should center the perspective of the crowd workers whose visual world we have entered.

In other words, the worker behind the camera should decide if an algorithm’s prediction is right or wrong in context. However, as social scientists know, concepts and labels are difficult; not all categories are distinct and not all miscategorizations are equally bad. For example, if an algorithm for object recognition sometimes identifies a soup bowl as a mixing bowl, that’s fine. But if it identifies the viewer’s child as a monkey, that is unacceptable and insulting. We can’t correct for this difference with some weighting scheme – the actual “badness” of a misclassification depends on context. If we really want to model the way individuals understand their visual world and whether an algorithm matches that, we need to enter that context, and engage with them qualitatively.

Qualitative evaluation requires dialogue with crowd workers: to capture video, to understand the way they understand the contents of the video and to determine which of several algorithms performs best in practice. By taking these steps, we yield epistemic power to these participants, and allow them to decide whose work earns the prestige of “state of the art.” The optimization objective of our modeling work ceases to be a gamified benchmark and turns into real humans’ approval.

When I’ve discussed this proposal with computer vision researchers, their response is usually, “isn’t that unscientific?” Disagreements like this have happened for decades in the social sciences; social scientists have turned to qualitative methods in order to better understand social phenomena in context. They argue that qualitative and quantitative metrics are better for different aspects of the scientific process. Qualitative methods allow us to test the assumptions behind our research in a way that quantitative methods do not.

In the context of computer vision, this sort of method allows us to evaluate not just our models, but the assumptions behind our problem statement, and ask us to think critically about who benefits from our algorithmic work. If a worker’s response is “none of these models really work,” that’s a valuable signal that we might be thinking about the problem wrong.

Of course, going to the same participants every time someone wants to try out a new model is impractical. These evaluations require everyone to be honest, as it is very easy to manipulate a subject’s responses, so they should not be required for publication. The evaluations also must include a broad range of participants to capture a broad range of perspectives. And no amount of talking to people will prevent unethical applications of basic research. But building feedback steps into the research process would go a long way to keep evaluation grounded in real world problems and warn us early of problems related to bias.

In the paper, we also provide an example of what this research looks like in practice using my dissertation work on aesthetic quality assessment. I’ll have a post about that soon, so I won’t discuss it here just yet. This is all very much work in progress, so let me know via the contact page if you have any questions or comments!