Teaching Historically Grounded AI

This semester, I was tasked with teaching our department’s AI course. The course had a troubled history: none of the senior faculty in my department are AI experts, so the previous two times the course was offered by an adjunct, so I didn’t have any standard to live up to and didn’t have a specific course design to start from besides a vague list of topics from the course description.

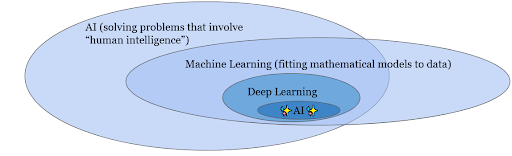

As a teacher, that scenario is like a blank check, I could teach whatever topics I thought were reasonable. The problem is that the scope of AI has exploded in recent years. What should a first course in AI for undergrads teach today? On the one hand, students want to learn about how modern deep neural network technologies like ChatGPT work. But that relies on a lot of background knowledge that is much easier to teach alongside older ideas about AI.

The approach I settled on relied on historicization. I designed and taught a historically grounded AI course including both classic topics, as well as a path connecting those topics to contemporary large language models. With a little help from my graduate advisor’s course materials (Thanks David!), the topics end up looking very similar to the classic “Norvig & Russell” AI course. But by organizing everything from a historical, person-centered perspective, everything made so much more sense, both to me and the students.

Why is an AI course difficult to design?

Recently, as everyone probably knows, AI, and student interest in it, has exploded. Over the past decade, AI has crept into virtually every subfield of computer science. That means, no matter what topics students are interested in today, AI is relevant to them. The discipline also has a 70-year history of mostly dead ends.

AI, a difficult term, also has become even more overloaded than before. At a recent social computing conference, I had a discussion with a variety of researchers about what they understood “AI” to mean. One person said that AI meant systems that took natural language instructions like ChatGPT. Another person said they thought AI meant any use of computerized decision-making. Another thought AI meant systems based on big data.

AI as a History of Practices

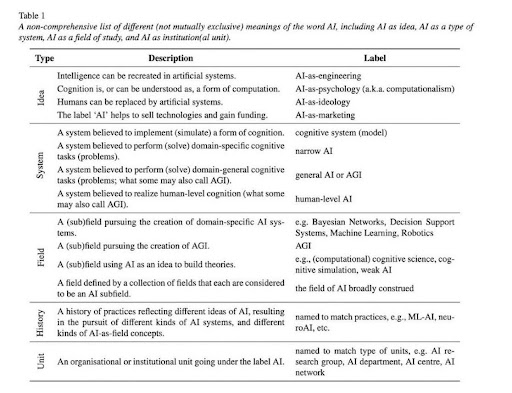

I found clarity in a recent paper by Iris Van Rooij about defining AI.

In this table, Van Rooij and her coauthors taxonomize many of the ways that people use the term AI today. I was particularly struck by the sense of AI as “a history of practices reflecting different ideas of AI, resulting in the pursuit of different kinds of AI systems.” In other words, AI is not a specific technology or scientific concept, it is a history of practices that lead to the pursuit of different kinds of AI systems. This is the perfect organizing concept of AI for an undergraduate course.

The Course Concept

The traditional AI course (i.e. taught before the deep learning revolution) is organized around search as its unifying concept. The class introduces search algorithms and then goes thorugh a variety of applications such as game playing, planning, automatic reasoning and learning and shows how each problem area can be turned into a search problem.

My concept was to organize the AI course around a timeline. Instead of treating “AI” as any particular technology, I treat it as a history, tied up with the cold war and the US military’s research funding system. While I’m not a historian and the class was a technical computer science class first, I found this approach helpful for organizing all the classical topics in a way that made sense to the students.

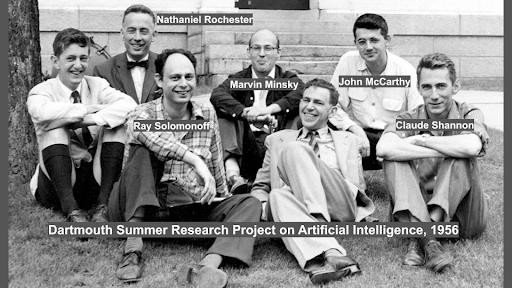

In the first class, I introduce different definitions of AI to the students, discuss the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence (which coined the term “artificial intelligence” so that they wouldn’t have to treat Norbert Wiener like a guru), introduce the “waves” of AI summers (periods with a lot of AI funding) and winters (periods with a lack of AI funding) and then discuss whether that narrative is really true. We specifically talk about the 1997 chess match between Gary Kasparov and IBM’s Deep Blue, which supposedly occurs in an AI winter, but required huge amounts of investment on the part of IMB.

By the third class, I introduce the story of Shakey the MIT robot and use it as an entrypoint to talking about search algorithms for pathfinding. We spend a few classes developing search algorithms such as depth-first and breadth first search and apply them to solve various logic puzzles.

Over the next seven weeks, I go through the standard AI course topics such as A* search, local optimization, the minimax algorithm, Bayesian reasoning and neural networks. I emphasize the connections to cybernetics and underlying utilitarian ethical framework behind the AI mindset. We then take an exam on the canonical topics from the first half of the course.

The second half of the course focuses on modern AI, with an emphasis on natural language processing. We talk about the rise of machine learning as an approach to AI and explore how three methods we have seen already: the Naive Bayes model, a softmax regression classifier and a multi-layer perceptron, all fit into the same framework of machine learning, and discuss the idea of training and test sets, loss functions and performance metrics. I also emphasize the number of parameters required for each model, and how the amount of training data and number of parameters are related.

The key concept that I teach for modern AI is the idea of a “latent space” where the actual dimensions are meaningless, but the similarity (often measured using a dot product) between the vectors for different inputs is meaningful. We see latent spaces for the first time with autoencoders, and then with word2vec. Exploring this concept in detail helps the students to understand convolutional neural networks and transformers in the next few weeks.

Along with convolutional neural networks, we talk about the history of the ImageNet challenge, how the University of Toronto team beat everyone’s expectations and talk about the immediate aftermath, when Silicon Valley quickly started spending a lot of money on deep learning research.

Finally, we discussed the transformer architecture, with an emphasis on counting parameters. After the students understand how many parameters there are in each weight matrix, we go through the successively larger language models of 2018-2023 and the students’ minds are blown by the scale of the successive GPT models. We finish the semester with two non-technical classes: one about social issues surrounding AI, especially related to bias and energy use, and another about fictions surrounding AI, including the myth of the AI apocalypse.

I really liked teaching this style of AI course for three reasons:

- The historical grounding gives a good answer to the question “why do we need to learn this?” Because it mattered at the time and influenced later researchers.

- It really gets the idea that AI is not some kind of fundamental science of intelligence (that label really belongs to cognitive science), it’s a history of programming techniques for solving problems.

- It teaches students to be skeptical about the kinds of narratives that AI companies and researchers tell about their work. AI research has historically had a lot of benefits, but those benefits never really line up with the promises researchers’ made along the way.

I got unanimously positive course evaluations (minus some grumbles about the math being too difficult), so this worked great, and I will definitely be using this framing again in the future.