Some Thoughts on Genre in The Incredibles

5/26/17

A week ago, I spewed some of my thoughts about The Incredibles in a post. Now I’ve graduated college and am back home with more free time. Hopefully, in this post, I can go through the rest of my ideas about the first part of Giacchino’s fantastic score.

Previously, I discussed the movie, my interpretation of it, and how the first scene and its music fit into that interpretation. I went on to go through three genre references that define the track, “The Glory Days” and its “Golden Age” style and speculate as to how they evoke nostalgia for classic comics. In this post, I want to look closer at some music-image mappings and see how they contribute to the central “Golden Age” theme of the track.

Music-Image Mappings

First, for some context, the paper I wrote on this music (that this post is an extension of) was for a class at Oberlin called “Music and the Visual”, which is, among other things, an introduction to music semiotic analysis. Music semiotics cares about music via its extra-musical associations: what does a piece (or melody, or chord progression, or interval, etc.) make us think of? My professor often quoted Brian Kane and said “all hearing is hearing-as.” When we hear, for example, the wood blocks and trumpet at the end of Leroy Anderson’s “Sleigh Ride”, we interpret it as a horse.

That mapping between a woodblock and trumpet and the sound of a horse is a metaphor; we can discuss it like any other metaphor in literature, and even get a better understanding of both sides of the metaphor (in this case, the sound of the trumpet and the sound of a horse) by doing so (see Lawrence Zbikowski’s Conceptualizing Music for more on these ideas). The mappings between music and non-music that occur in Giacchino’s score that I want to discuss fit into two categories, mickey-mousing and leitmotifs.

Mickey-Mousing

The first kind of mapping we will discuss is Giacchino’s use of mickey-mousing in the piece. Mickey-mousing is the practice of matching the music for a segment of film to what is happening on screen, where each action or emotion that occurs is clearly represented in the music. For example, this classic Tom & Jerry episode:

The practice was named for its use in early Mickey Mouse cartoons, and generally has a negative connotation, since mickey-moused scores add very little to the film they accompany. Mickey-mousing, though, makes a scene very easy to follow, since both the soundtrack and the score reinforce what is happening on screen on a very literal level.

Giacchino makes heavy use of Mickey-mousing in this scene, a list of occurrences of Mickey-mousing and Leitmotifs is in the table below. While Giacchino’s uses are not as explicit as instances of mickey-mousing in cartoons, they still fit the definition because they directly translate action onscreen to music.

They are also more diverse in terms of musical devices: Giacchino is not just writing music that sounds like what is happening on screen. For instance, the examples at 0:18 and 0:25 involve changes of musical texture to match action, the examples at 1:25 and 2:51 use silence and examples at 1:02 and 1:41 use musical ideas that sound like motion.

Here’s the scene again if you want to follow along:

| Time | Mickey-mousing or Leitmotif? | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0:07 | L | 3+3+2 in bass for car chase |

| 0:18 | M-M | Volume decreases significantly the shot changes from outside the car to inside |

| 0:25 | M-M | Brass enter as Bob pushes the transformation button in his car |

| 0:37 | M-M | Saxophone solo accompanies Bob letting go of the steering wheel |

| 0:43 | L | Mr. Incredible theme returns exactly as the logo appears on his chest |

| 0:51 | L | Theme returns again as the car transforms |

| 1:02 | M-M | Full brass forte-piano as Mr. Incredible gets a jolt of adrenaline and brakes |

| 1:16 | L | 3+3+2 bass pattern returns as car chase comes into view |

| 1:25 | M-M | Music cuts out as camera zooms out, Mr. Incredible remembers the car chase |

| 1:25 | L | Robber theme and 3+3+2 motif appears as car chase comes into frame |

| 1:41 | M-M | Low brass play a loud note as the tree comes down on the robbers’ car |

| 2:31 | L | Robber theme returns quietly as robber appears on screen |

| 2:43 | L | Mr. Incredible theme returns as his shadow appears onscreen |

| 2:51 | M-M | Horns crescendo, then cut out exactly as Elastigirl’s fist hits the robber |

| 3:34 | M-M | Harp mimics Elastigirl’s jumps from building to building |

I think mickey-mousing has an onomatopoeia quality, which gives this music a further similarity to golden-age comic style. Comics use characteristic onomatopoeia like “zap” and “kapow” (which are themselves a mapping between written text and sound) to exaggerate illustrated actions. Mickey-mousing adds similar exaggeration to actions and, in doing so, draws the comparison to comics. This similarity between mickey-mousing and comic onomatopoeia has precedent in the 1966 Batman TV show, which used both written onomatopoeia on screen and musical indications (usually trumpet hits) to exaggerate physical combat.

Leitmotifs

Now that I’ve talked about mickey-mousing, the other big music-image mapping is through the use of leitmotifs, or theme music. The concept of a leitmotif goes back to Ricard Wagner, who had melodies or harmonic ideas that would play whenever a character appeared or a concept was discussed in his opera cycle, Der Ring des Nibelungen.

Leitmotifs are similar to theme songs, but are a little more subtle: they are usually not the main focus of the musical texture and serve to annotate the narrative, reminding the audience which character is which, reinforcing mentions of people or things that are offscreen, or making commentary, like playing the melody for one character when another character is onscreen to draw a comparison between the two.

Giacchnio uses three main leitmotifs in this track, their locations are in the table above. They include:

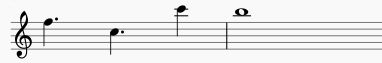

The “Mr. Incredible” theme:

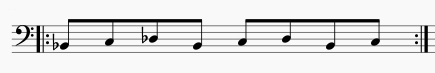

The “Chase” motif

And the “robber” motif

Leitmotifs, in addition to providing a general nod to film scores, add to the Golden Age style by helping the audience know how to feel. When we, as the audience, hear the Mr. Incredible theme from the title screen return as Bob transforms, even though his logo and color scheme are different (since this scene is set in the past), we know that he is our protagonist. Hearing the robber theme return tells us that this person on top of a building is a robber. Whether we hear the chase ostinato or not signals to us whether the focus is on the car chase or not.

Subtle hints like these make the movie easier to follow, mimicking the simple, easily followed good vs. evil narratives in Golden Age comics. In the rest of the film, Giacchino does not give us such clear signals, and as a result it is harder to tell good from evil and right from wrong.

Conclusion

The Incredibles is a wonderful movie with extremely strong visual and musical style. While I’ve spent a lot of time discussing the musical style, and how that reinforces the golden-age comic aesthetic in the first scene of the movie, I haven’t said anything about the visuals. There’s a lot being done with animation style, camera angles and lighting that reinforces these same ideas that are just as interesting, but as a music theorist, I’ve stuck to what I know (this article discusses the visual style and how it dodges the “uncanny valley”). I’ve also neglected to mention the rest of the score, which does plenty of other things musically.

I’m also super excited to see how these stylistic choices continue in Incredibles 2, coming out next year! Giacchnio is still scoring it, so it’ll probably be just as good.

Those are my feelings about the Incredibles! Thank you for reading my ravings, hopefully some of what I talked about made sense and will help you appreciate film music in a slightly different way. Additionally, if anyone who comes across this post has any feedback on my writing style or content (did anything read awkwardly? Did anything not make sense?) feel free to email me at the address on the sidebar.