Models of the Self in Disco Elysium

In this post, I’d like to examine an unusual text:

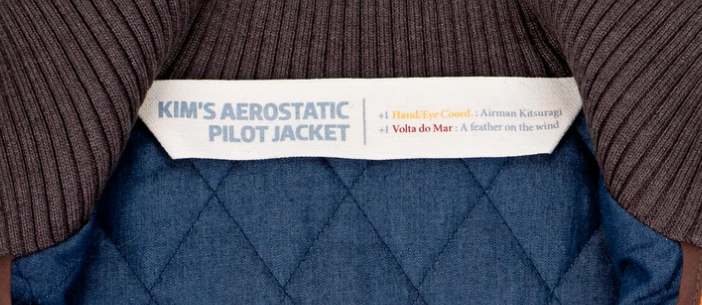

(image from Reddit)

This is the label on a designer jacket produced by ZA/UM, the art collective and video game studio behind the hit 2019 game, Disco Elysium. It reads:

Kim’s Aerostatic Pilot Jacket

+1 Hand/Eye Coord.: Airman Kitsuragi

+1 Volta do Mar: A feather on the wind.

The jacket is a replica of the one worn by a character in the video game, Kim Kitsuragi.

The official photo for the garment, Source.

Since this text is written on a garment which is itself a spin-off of a video game, understanding what this text is saying requires quite a lot of context. In this post, I will provide six different pieces of context which have shaped my interpretation and then make the case that this short text puts forward an interesting approach to modeling individuals with implications for machine learning.

Context:

I.

In the era of big data, we can collect a lot of information about people. Sometimes that data is relatively consistent from person to person, like the patterns of accelerometer data that corresponds to a step. Other times, it varies quite a bit from person to person, for example, our preferences in media, our social media activity or our diet. In these situations, it is tempting to try to model the user as some kind of random variable, with some high dimensional parameter that explains their behavior. Let’s call these parameterizations “models of the self.”

Such models are essential for personalization. Simply, if we want our computer programs to function differently for different individuals, we need some way to describe how individuals actually differ from one another. Collecting personal information has boomed into a huge industry in the 2010s and 2020s, and it is unclear what kinds of personalization are legal or ethical, as we traditionally consider the self as something internal, personal and private. Still, models of the self are in common use today, without much regard for their philosophical or psychological implications.

II.

One key application of models of the self is in what the computer scientist and new media scholar Judith Donath calls “Data Portraits” which depict users in digital spaces. These can be profile pages, like you find on social media websites, or more sophisticated visualizations, like “People Garden” reproduced below:

Here, the stems, flower sizes and shapes correspond to how long a user has been participating in a forum, how often they contribute, etc. In this sense, the data and visualization describe each person as a forum user, rather than as a whole individual. The name draws a connection to the concept of a portrait in fine art, which also depicts certain aspects of the subject’s personality, as well as their appearance. Ultimately, it’s up to the painter to determine the best way to reduce a three dimensional person with a much-more-than-three dimensional persona into a two dimensional portrait.

Portraits (both data portraits and the fine art variety) are also models of the self. They try to come up with some system for translating individuals in all their complexity into something simpler which is easy to understand at a glance and highlights some kind of significant difference between them. A painted portrait might have a dog in it, or fashion the subject in a ballroom gown, or playing a musical instrument. These are simple symbolic stand-ins for complex elements of a person’s identity, in addition to their literal appearance. Similarly, a social media profile might show a user’s picture, some of their pinned posts and a brief autobiographical description. In both the traditional portrait and the social media profile, some elements are symbolic stand-ins while others show the person’s literal appearance.

III.

Another place where models of the self come up is in role playing games. At the start of a game like Dungeons and Dragons, each player creates a character, filling out both quantitative (e.g. their strength score) and qualitative information (e.g. their social background) on a character sheet. The character sheet ultimately becomes a model of the character, parameterized by all sorts of attributes, abilities, skills and traits. It also serves as a guide for the player, helping them decide how their character will interact with others and react to things happening in the world.

While role playing game characters are poor models of people in the real world (humans don’t suddenly gain magical powers as they defeat monsters in combat, for example), they raise an interesting question: if humans could be reduced to a simple collection of statistics which describe who they are, what should those statistics be?

IV.

Physicians and psychologists have come up with several answers to these questions and have a variety of statistical models which describe people. Blood pressure, body mass index, resting heart rate and a whole host of medical condition labels serve as a practical model of the self, at least in a physical sense. To describe the mind, psychologists have developed their own similar models, including a variety of different personality systems, IQ scores and diagnoses.

Despite their useful qualities, these models are often seen as dehumanizing, objectifying and reductive because they encourage humans to treat other humans as statistical objects with well-defined properties, rather than complex individuals. Some of these models are also normative and prescriptive: they do not just assert that a variable like blood pressure is useful for describing a person, they also specify a normal range of blood pressures and instruct people whose values fall outside that range to change their behavior. While these recommendations might be based on good medical evidence, they encourage physicians to ignore the patient as a human in context and use the model instead. In my experience, I’ve certainly received medical advice which feels deterministic given a measurement and completely removed from the context of my life. Though I’m not a medical researcher and have no evidence for claiming that my doctors are making recommendations based on a model.

V.

Disco Elysium is a video game developed by ZA/UM, an Estonian art collective and game development studio. In the game, you play as a police officer, Lieutenant Harrier “Harry” DuBois, who wakes up in a hotel room, hung-over with total memory loss. Over the course of the game, Harry must juggle discovering the culprit in the murder he was sent to investigate while also discovering himself and learning why he almost drank himself to death. Along the way, the game takes us on a journey through political ideology and personal identity, as it turns out that the murder was intimately connected to a labor dispute, between a multinational shipping company and the local dockworker’s union, though ultimately love was a more significant factor.

Along the way, Harry becomes friends with Lieutenant Kim Kitsuragi, a police officer from another district assigned to the same murder investigation. As they investigate together, Kim serves as a foil to Harry: he is a mild-mannered and thoughtful detective and while he doesn’t hold strong ideological opinions, he has a strong sense of right and wrong, unlike Harry who can hold whatever opinions we, as the player, makes him. Kim’s character is essential to the narrative, as he brings Harry’s internal struggles back to reality, and serves as a straight man for Harry’s sometimes bizarre antics.

The part of the game I find most interesting, however, is the way Harry is modeled. The game makes use of a system of 24 skills such as “logic” which determines your character’s ability to put facts together, “espirit de corps” which governs your knowledge of police culture and protocol or “physical instrument” which governs your brute strength.

Disco Elysium’s skill system, a model of the self, or at least of the game’s protagonist.

To some extent, Harry is a blank slate. You, as the player, can choose to improve whichever characteristics you like, and his problem-solving and demeanor will change. But the skills available and the way that they are organized constrain your character’s choices. He is still, ultimately, a product of his personal and professional history as a washed up, alcoholic, disco-loving police officer.

VI.

In many role playing games, characters have magic equipment which increases their abilities in the game mechanics. For example, in Dungeons and Dragons, your character can wear a Belt of Giant’s Strength which increases their strength. Typically, these changes to your character are explained through magic: the belt has a magic enhancement which actually allows your character to lift heavier objects and hit harder in combat.

Disco Elysium has a different take on the same concept. Its pieces of equipment still increase Harry’s skills, but they are just ordinary articles of clothing. Rather than magical enhancements, they are entirely psychological: a pair of “flair-cut trousers” for example has the description “+1 Electrochemistry: Tight around the crotch, -1 Savoir Faire: Tight around the thighs.” +1 Electrochemistry means it increases your electrochemistry skill, which increases Harry’s benefits from drugs and encourages him to act in the pursuit of physical pleasures. -1 Savoir Faire means it decreases your Savoir Faire, which is French for “know to do” and idiomatically means knowing how to act in a social situation. In the game, -1 to Savoir Faire means Harry is less effective when sneaking, and less smooth in conversation.

(source)

I find this model absolutely refreshing because it captures how clothes affect us in real life through role playing game mechanics. Clothes change the way we interact with the world, not because of magical enchantments, but because of how they look, how they feel on our skin and how they affect both the way others see us and the way we see ourself. The game takes the common expression “the clothes make the man” very literally: clothes are a key component of Harry’s self within the game’s mechanical system.

My Interpretation

With all of that context in mind, let’s turn to the designer jacket released by ZA/UM:

Kim’s Aerostatic Pilot Jacket

+1 Hand/Eye Coord.: Airman Kitsuragi

+1 Volta do Mar: A feather on the wind.

The jacket is a replica of the one Kim Kitsuragi wears in the game. The text is short and surprisingly poetic: “Airman Kitsuragi” and “A feather on the wind” both have six syllables and alternating stress patterns, which gives the words a bit of ebb and flow. In terms of meaning, the label is written in the style of the other item descriptions: it increases the wearer’s Hand/Eye Coordination, which is a skill that allows Harry to catch flying objects and shoot accurately. Volta do Mar, however, is not one of Harry’s skills. The phrase is Portuguese for “turn of the sea” and it was the name of a sailing technique during the Age of Discovery where sailors who were traveling north along the west coast of Africa would instead sail west, past the Canary Islands, and use the trade winds to return to Portugal.

This text raises fascinating implications for Disco Elysium’s model of the self. In the game, we only ever see mechanical text for items that Harry can wear, and all of their mechanical effects are defined in terms of Harry’s abilities. Volta do Mar doesn’t appear in the game at all, since it’s not one of Harry’s skills. We can speculate about what Volta do Mar does: perhaps it helps Kim approach problems from unusual perspectives, or stay light on his feet. The exact effect is unknowable, because while Kim is a significant character in the story, he is not a player character in the game world. All of his actions are scripted, and since we experience the world from Harry’s perspective, we cannot see inside his mind.

The significant factor here is that the appearance of this text on this garment implies that Kim has a different collection of abilities from Harry, which means that all of the other characters likely have similarly different statistical systems governing their abilities and behaviors in the fiction of the game (though not in the game’s actual implementation). This fact would make Disco Elysium’s quantitative model of the self very different from role playing games like Dungeons and Dragons. In most of these games, the statistical model that describes characters is constant, the characters define their differences by the particular values of their attributes. Because the model describes all characters, it functions like IQ or BMI: a statistical model which fits different individuals into the same framework. But Disco Elysium clarifies, in only this jacket label, that the statistical model that describes Harry is only valid for him. Disco Elysium’s statistical system thus functions like a true data portrait: it’s a whole data schema which perfectly describes an individual.

The idea to avoid placing all characters into the same statistical framework is not their invention. A variety of role playing games feature flexible stat systems, for example, the HeroQuest system avoids specifying a specific space of attributes entirely and instead places more weight on keyword descriptors for each character. Flexible RPG systems, however, usually do so by avoiding fixed parameterizations for their characters and allowing things to be more ad-hoc. But Disco Elysium does use a fixed parameterization: its system not only describes who Harry is, but all of the ways that Harry can be. As a player, we have freedom to choose Harry’s demeanor, strengths and weaknesses within the constraints of the model, which are defined by factors outside our control.

This kind of model embodies a critical view of the self. On the one hand, Harry is not a detached, rational, Cartesian mind, or an ever-negotiating Freudian ego. The mechanics which govern his thoughts are both a product of world history, and a product of his personal past, even when he cannot remember either directly. Harry’s sense of self emerges out of his interactions with others, and his identity only becomes defined as he encounters opportunities to define it. But he still has freedom, in a sense. Harry (or the player, roleplaying as him), can seize agency and choose what he believes and how he should act. While I haven’t read Lacan, I’ve been told that these ideas echo concepts from Lacanian theory about the nature of the self, the unconscious and free will.

Implications for Personalization

I think we can take inspiration from this model in machine learning and the study of personalization. Quantitative models of the self, like BMI, are usually dehumanizing and reductive because they try to force different individuals into the same framework, even though they exist in different contexts. Qualitative models of the self, like personality types, however, tend to be so vague that any type could apply to anyone, and thus it says relatively little. What if instead we used different models for different individuals, then learned the parameters from data? While this isn’t quite what Disco Elysium does (it hands you a model structure perfectly fit to Harry and has you choose the parameters), it embodies a similar concept of the self.

This line of thinking makes me think that scholars of computational modeling, especially in social contexts, should really be thinking about role playing games. RPGs exist on a continuum with other kinds of computational models for people: while they are subject to different constraints (e.g. they must be part of a game that is fun to play), they are ultimately elements of the set of possible models of the self, alongside models used for advertising, psychology and medicine. Games give us a way to explore quantitative models qualitatively.

In other words, when game designers create RPG systems, they can explore new kinds of character models in the same way that composers can explore new concepts of consonance and dissonance, or playwrights can explore new kinds of character dynamics. When we play RPGs, we breathe life into those models and live in them for a while, much like musicians breathe life into a piece or actors breathe life into a play. So rather than create models as engineers, what if we created them as game designers and evaluated them through playtesting, rather than performance metrics?

These ideas point towards two broad goals in my research.

First, I want to explore ways of doing machine learning which treat optimality and optimization as a means, rather than an end. I’ve written about this topic at length in my post on optimizationism, the idea is that I think organizing our disciplinary value systems around optimality presents a huge barrier to interdisciplinary collaboration with artists and humanists.

Second, I’m interested in approaches to subjectivity in machine learning which are less reductive. Most machine learning approaches to subjective problems, like measuring visual similarity or colorizing photos, either treat one answer as objectively correct, treat subjective differences as random noise or try to reduce individuals to a few parameters. I haven’t posted about these issues in as much length, but I’ve got a paper about this topic on the way.

Anyway, I like Disco Elysium and how it plays with RPG mechanics and the self, and I felt the urge to analyze this jacket label, but I’m not really sure what to do with these ideas. If you have any suggestions, or have a related project idea, send me an email at the address in the sidebar! I’m always happy to chat about personalization, mixtures of qualitative and quantitative research or RPGs.