Aesthetic Phenomenon Problems

I defended my dissertation! If you want to read it, you can download it here (caution: 18MB, 240+ page PDF).

In this post, I’m going to describe its key unifying question: how do we evaluate algorithms for aesthetic phenomenon problems in computer vision?

You know it when you see it…but does a computer?

In 1963, US Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart wrote that the first amendment protects everything except “hard-core pornography” and, while he doesn’t define that term, “I know it when I see it.”

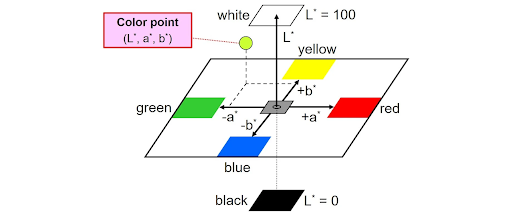

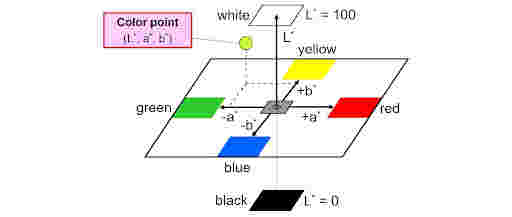

There are a lot of things we know when we see, but find difficult to precisely define. Take, for example, colorfulness. How should we measure colorfulness in a digital image? Everyone knows what it means for a painting to be colorful, but when you get into the weeds trying to define and measure it, you run into a whole world of complexity.

Which of these Mark Rothko paintings is more colorful?

This difficulty isn’t just limited to “artistic” properties either. An important topic in image processing is measuring perceptual artifacts, like the distortion in a JPEG image of a screen.

The right has JPEG compression artifacts, which distort the image around sharp lines.

There are a variety of computational methods, of varying levels of complexity, for measuring this distortion in an image. For something that seems so obviously visible, we’d expect there to be an easy way to measure it. But because it depends on human perception, people practically disagree about what distortions are perceptible and how much they matter. Engineers have spent countless hours figuring out metrics for these phenomena, but there is no best metric.

These two concepts, colorfulness and perceptual artifacts, are aesthetic phenomena. They are qualities that we feel because of images, but they are not fully contained within the image itself. When we try to write computer programs that measure aesthetic phenomena, we are trying to solve aesthetic phenomenon problems. Those solutions are called aesthetic measures. In my thesis, I explore a couple of these problems, and then go very deep in a discussion of one of these problems: image aesthetic quality assessment, or the task of determining whether a photograph is “high aesthetic quality.”

Subjectivity in Aesthetic Phenomenon Problems

These problems are very difficult to work with because they rely on human perception, which is difficult to measure. We can’t put a sensor in someone’s head to figure out what they see, so we have to rely on talking to them and asking them how something looks. But how something looks depends on context: it’ll be different in a lab vs. in the real world, different based on who is asking and why and even sometimes different from person to person.

Difference from person to person is subjectivity, which is a dirty word in the sciences. Scientists want to generalize, we want to find fundamental laws which are true for everyone everywhere. With these problems, it’s not clear that such a thing is possible. How do we know our solutions are right for everyone? What if this model is only correct to the experience of the researchers who developed it? Typically, researchers working on these problems try to avoid subjectivity and argue, using data from many human participants, that their metric is the best one.

But humanists have been thinking about subjectivity, and how we can account for it in our knowledge, for hundreds of years! Computer vision, like psychology and cognitive science, has historically rejected the philosophical study of perception as unscientific. But if we want to blur the boundary between objective and subjective aspects of vision, we need to be willing to also blur the boundary between scientific and unscientific knowledge.

Practically, that means recognizing two forms of subjectivity:

- Subjectivity in the data: “which Rothko painting is more colorful?” When we ask people to rate a phenomenon on a scale, sometimes they answer differently due to subjective factors. We can account for this form of subjectivity using inter-rater reliability metrics and robust statistical models.

- Subjectivity in the model: “is colorfulness continuous or discrete?” When researchers decide how their statistical model works, they use their own subjective experience and intuition as a guide. This subjectivity is more infrastructural, and we can partially account for it by showing the results of our modeling to other people and getting their feedback.

We have to account for these forms of subjectivity when we are performing evaluation, checking whether our algorithms actually measure the qualities we claim that they do. If we fail to account for subjectivity both in our model and in our data, our models will reflect a specific worldview which may be wrong or nonsensical to some users. I think failing to account for subjective difference is a major source of algorithm bias in vision algorithms.

Evaluation for Aesthetic Phenomenon Problems

Typically, in the field right now, we measure the performance of algorithms for aesthetic phenomenon problems by taking a collection of images, asking humans to rate each image, then using our algorithm to compute a score for each image, and measuring how well the scores from our model correlate with average scores from the humans.

In the thesis, I explore what happens when people disagree about these scores. It turns out our algorithms will naturally do much better for some people than others. Drawing on arguments made by feminist theorists, I claim that those differences are important and worth studying. Instead of trying somehow to account for subjective difference algorithmically, we should accept that the performance of our algorithm is subjective and take a more human-centered approach.

Practically, that means making these algorithms tangible things that a person can judge, and letting human participants compare them to one another. We did that for aesthetic quality assessment algorithms by building them into a camera app. The app has no shutter button; instead it takes photos when an aesthetic measure exceeds a threshold, shown in a line plot above the photo preview.

This video is a little choppy, but hopefully you get the idea.

This method is really effective for soliciting feedback about not just the different models, but the problem statement as a whole. The key element is that instead of evaluation being a binary “correct” vs. “incorrect” we can talk about the concept under study and get to know how our participants understand that concept. This sort of perspective-taking is really new in computer science, but I think it will be increasingly important going forward.