When Algorithms Approach Subjective Problems,

Who Are They Correct For?

Subjectivity is a bit of a dirty word in machine learning. We aspire to be a highly objective, mathematical, scientific discipline. That means we want to make our algorithms and evaluations as objective as possible. In many cases, we can formally define the problem at hand and prove our solutions correct. In other cases, we can’t really define the problem, so we collect data and use that data to evaluate our methods empirically. But does evaluation based on data really work when the underlying problem is fundamentally subjective?

Along with my advisor David Crandall and our postdoc, Weslie Khoo, I decided to investigate this question using a test problem: personalized aesthetic quality assessment. This computer vision task asks an algorithm to learn what the user considers to be a “good” photo and measure the quality of such photos automatically. This problem gets deep into questions about taste which are completely subjective! But the authors in this space use the same sort of evaluations that are used for more objective computer vision tasks.

We thought that was a little sketchy, so we ran a survey and wrote a paper with both lots of philosophy and lots of data analysis, which just got accepted to AAAI 2023! If you’re interested read our paper! This whole topic is esoteric for lots of different reasons, so I’ve attempted to explain it below.

Personalized Image Aesthetic Quality Assessment

The view out my window, overexposed and blurry. Is this a bad photo?

Imagine you’re out on vacation, taking tons of photos of all the people, places and things you see. Unfortunately, you’re not a great photographer, so most of the photos are really bad: some are blurry, some are off-center and many just show the inside of your pocket! Wouldn’t it be nice if you could tell your camera (or camera app) to delete those really bad photos and free up space automatically? AI researchers have made this a reality through algorithms for aesthetic quality assessment (which I’ve written about before).

A photo of the inside of my pocket. While most people might think this is a bad photo, can you predict whether or not I’ll like it?

If the idea of an algorithm choosing to delete your photos worries you, you might be surprised to learn that your smartphone is doing something similar already! If you don’t believe me, try to take a bad photo. If you have a recent-generation phone it will actually take a short video and select the best frame, according to a few simple metrics, and all the potential bad photos you could have taken will be suppressed, so every photo turns out good (according to the algorithm’s implicit definition of “good”). Even though it might seem like you took the photo, it’s really more like AI art: a collaborative effort between you and the software.

Something’s Fishy

But whether a photo is good or not is fundamentally subjective! What if you disagree with the algorithm’s implicit sense of taste? This question has led researchers to recently investigate personalized aesthetic quality assessment. These algorithms learn from a few examples to make predictions about whether you, the user, will consider a new photo “good” or not.

We can build a model to do just that, but does it work? Can we actually learn someone’s taste from just a few examples of photos they like or dislike? To answer that, we need data to measure performance. Other researchers have satisfied this need, providing datasets with plenty of users’ individual preferences for images. But none of these datasets have much in the way of study details or information like demographics about the participants. Also, we’re not sure that asking people to rate images on a five or ten star scale actually tells us how much they like those images.

A photo of the Kandinsky print on my wall. I moved the camera during the milliseconds-long sensor read from top to bottom. When I took this photo, my phone automatically selected a neighboring frame that was less blurry.

The Philosophy Section

Ultimately the way of thinking about subjectivity and aesthetics used in this research has its roots in 18th century philosophy. During the Enlightenment in Europe, there was great interest in using ReasonTM to overcome our differences and find concepts of taste which were unbiased and democratic. Immanuel Kant had an influential approach: he claimed that our opinions about beauty only differed because they were “bound up with interest” meaning that they depended on material things like our desire or pleasure from looking. Beneath our opinions, Kant claimed, there is a rational disinterested taste which all rational people can access if they think carefully about it.

This research area implicitly approaches subjective difference from a Kantian perspective: they average together many worker’s ratings as an objective rating for an image, and attempt to explain each person’s difference from the average using external factors like preference for different photographic qualities or content, demographic factors or personality types. While they aren’t thinking about “interest” exactly like Kant was, the underlying ideas about rationally explaining how taste varies are the same.

This is interesting because many later philosophers have criticized disinterestedness, particularly feminist philosophers. They point out that the supposedly neutral disinterested perspective still seems a lot like an 18th century rich, educated European man’s perspective. For instance, Kant claims that there are universal, rational reasons that women can only engage with some kinds of emotional experiences in art. His contemporary Edmund Burke famously deduces why light skin is inherently more beautiful than dark skin. These rational deductions are clearly not true! Feminist theorists argue instead that there is no such thing as a neutral perspective about art. No matter how you approach it, you’ll always be closer to some people’s views than others, and views that seem neutral and based in “common sense” might really be a product of your culture.

But does this philosophical argument extend to contemporary machine learning models? We did a study to investigate, the short answer is yes. If you took my survey about a year ago, thank you for your help!

Our Study

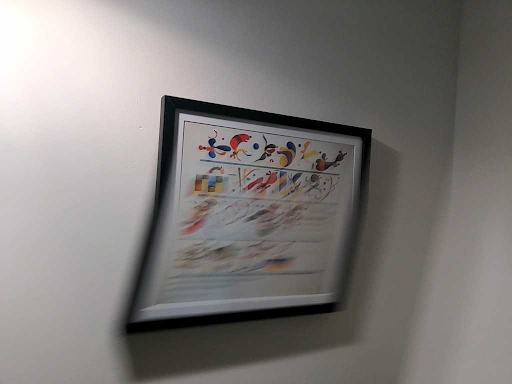

We showed around 200 people a series of pairs of images, and they had the option to select which image they enjoyed more. Each person saw the same first 20 pairs of images, then saw 80 pairs that no one else saw.

All of these images were taken from an existing dataset, the aesthetics attribute database (AADB) assembled by Shu Kong while an intern at Adobe research. That gives us the unique opportunity to assess whether the “correct” answers on those images (according to the ground truth labels published with the images in the dataset) actually predict our users’ preferences. And, if not, whether the differences are easy to predict.

We found that the accuracy of the original ground truth labels varies a ton from person to person. For some of our participants, the original labels predicted their choices upwards of 55% of the time! But for others, the original labels predict their choices less than 30% of the time, which is worse than even random labels. And, we found difficulty predicting that accuracy based on other factors. Disagreeing with the ground truth labels was not simply a result of gender or education level, for example. There are lots of details, read our paper if you’re curious.

This mostly confirms that the feminist critique of Kantian disinterestedness applies to this contemporary machine learning problem. In matters of taste, there is no such thing as a neutral perspective, even if we take an average of many peoples’ viewpoints and it is very difficult to predict how someone’s taste will vary from that average. This position is coherent with the ideas of D’Ignazio and Klein’s data feminism: no matter how much data you collect, your knowledge about the world is still positional.

How Should We Approach Subjectivity in Machine Learning?

I think there’s a broader issue at play here. Many machine learning problems in computer vision relate to subjective qualities, things like beauty, similarity, healthyness, cuteness or colorfulness. When we develop algorithms to measure these qualities, we can’t evaluate them by asking people to rate images, then check that we’ve learned something vaguely resembling an average “human” perception. If we do that, our model evaluations will vary based on who we ask, especially if our goal is to build something that personalizes reasonably well for all users, not just ones who think like the ones initially surveyed to create the benchmark.

The kicker is, subjectivity is hiding in lots of places. For example, imagine we’re designing a voice assistant who speaks in casual English, and personalizes its speech to the speech of the user. There is no neutral version of English, different people speak with different regionalisms, accents and subtly different senses of grammar. If we want to evaluate the performance of such an algorithm, we’ll need a representative sample of all variants of spoken language to test on, otherwise we will overfit to specific regions. Just showing that our model personalizes to many different users isn’t good enough.

We can also find subjectivity in a lot of the really interesting parts of deep learning. For example, we’d like embedding spaces, especially the ones we use for retrieval problems, to encode some concept of human “perceptual similarity.” But there is no neutral way humans perceive similarity! Like beauty, humans intuitively organize their experiences in different ways, and evaluating the quality of an embedding turns into the same problem. While an embedding can be objectively useful for a prediction task, claiming that it aligns with some notion of “human” perception requires us to think about all the different ways humans see the world, and whose perception we’re aligned with.

Anyway, I’m writing my dissertation about these issues. Stay tuned for more details!