Is There a Human-Centered AI Art?

I had the privilege in December of participating in the MosAIcs symposium at Washington University. It was a fun event, involving contemporary mosaic artists, neuroscientists and computer scientists interested in aesthetics. My talk framed some of my research in terms of the question: is there a human-centered computational aesthetics?

(I’ve given this post a more attention-grabbing title, If you’re only interested in the AI art stuff, scroll down here)

By “computational aesthetics” I mean computational models that attempt to predict what images humans will like. In particular, I’m interested in “image aesthetic quality assessment” models which take an image as input and output a number. These models are fit to image-label pairs from a large dataset, such as the AVA dataset, and are used to curate images for large AI art datasets. For more about which humans, and what these models actually do, you can see some of my previous work.

By “human-centered” I mean something that is useable and intuitive to human users, particularly working artists, attempting to complete a task, in this case, free creative expression. In this post, I’d like to take this concept and connect it to related ongoing debates about AI art.

What use does computational aesthetics have?

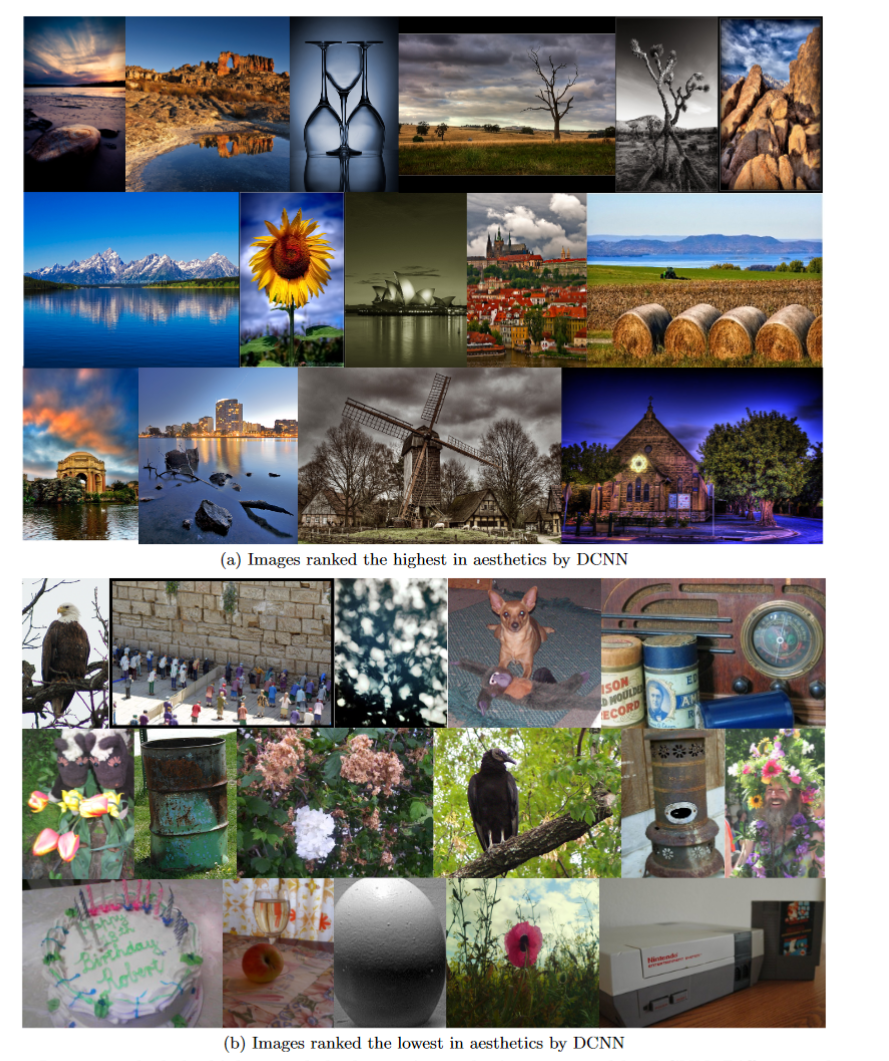

Historically, compuatational aesthetics was kind of a “delightfully useless” field. But recently, as AI art has gained mainstream interest, it has become useful for at least one thing: curating training data for image generators so that the generators only produce “aesthetic” outputs.

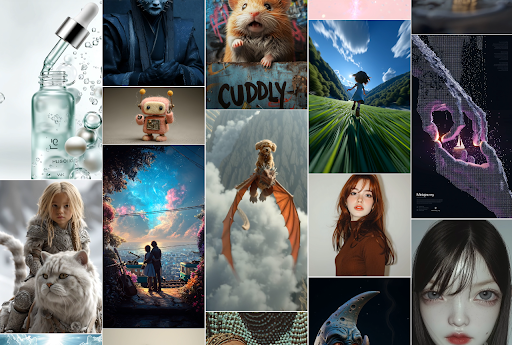

This is, at least in part, why AI art looks the way it does. And the too-perfect ugliness of AI art, to some extent, can be blamed on the failure of these models to learn any real concept of the aesthetic. Instead, they learn a particular “aesthetic” style which is carried through to the generated images.

How do we evaluate these models?

I believe that the issues with these models come down to a failure in evaluation. We evaluate AQA models by measuring their accuracy on a held-out set of test images. That means:

- We collect some images

- We ask people to rate those images

- We average their ratings

- We train a model and run it on the same images

- Then we compare the model’s scores to the average ratings and see how many it got wrong

This is completely backwards! Human preferences are not nearly as stable as the computer programs that model them. And humans are much better at judging things directly. So I did a project building a system for humans to evaluate aesthetic quality assessment models directly in the form of a smartphone app. The app is a camera app, based on OpenCamera, with no shutter button. Instead, it takes photos when one of several aesthetic quality assessment models highly rates the image in front of the camera.

The result is an app that is completely annoying and difficult to use. But the ways in which it is difficult to use help us understand the limitations of each model. In particular, participants try to understand why the model takes some photos and not others. When models are legible, meaning that their decision rules can be easily read by a participant as a sense of taste, users feel like the system is working. When models are illegible, users find the system random and nonsensical.

What this means is when you put AQA models into ordinary people’s hands, they start to build robust mental models of performance and give rich descriptions, which are much more informative than benchmark scores. Even though these judgments are subjective, it’s not like there is an objective way to evaluate aesthetic quality assessment anyway.

Our participants also tended to connect their evaluations to their prior experience with photography, apps and aesthetics. In particular:

- BeautyCam apps that edit photos in real time to add the appearance of makeup and remove blemishes

- photo editing apps where they can improve bad photos

- social media apps (in particular instagram)

My takeaway from this research is that aesthetic quality assessment models are only as usable as they are legible to users as models of aesthetic quality. I also argue that we should not be considering computational aesthetics separately from gender, culture, technology or power.

Ok so is there actually a human-centered AI art?

Yes, there can be, but in order to create it, we need to start trying to build systems that are useful for people, rather than trying to build artificial people.

In other words, attempting to model human perception is valuable research in the abstract, but the logical conclusion of that research direction is a computational model that can perfectly predict what I will feel when I look at a photo, and that won’t result in a human-centered technology. Instead, we should build new kinds of systems for curating images and let people use them and give feedback, especially people with artistic training. It is exceedingly difficult to curate large datasets of images, and computational curational tools would be much more useful to real people than tools attempting to measure what any person or group considers “aesthetic.”

Three principles for a human-centered AI art

I’m not sure there will ever be a fully artist-centered AI art, as any system to create images directly competes with working commercial artists, in the same way that photographers initially competed with portrait painters. But it is still worth thinking about what sorts of ways we can better center artists as users. I think AI art could do much better to center artists, rather than businesspeople.

The following principles aren’t particularly scientific, they’re just my instincts based on my background as a musician, researcher and professor, and some informal conversations over the past few years with amateur and professional artists. I think they are all within the realm of technical feasibility.

1. Give users full control

AI image generators are running on servers owned by a company, which makes them inherently hostile to free expression. If users are engaging in serious creative work, they should have total control over the training data and training process. It should be possible to build an image generator model, for example, without accidental use of any image scraped from the web. It should also be possible to curate large sets of training images in a personal way, rather than only use the largest datasets with the broadest possible appeal.

The vision that I have is a collective approach, where training images, software and hardware are owned, contributed and curated by a studio of working artists. It’s not unusual for an artistic studio to have specialized hardware, like a kiln or press, for a specialized artform. Computer animation studios owned powerful computers long before individuals could, for example. There are serious arguments to be had on this topic regarding images that we do not want to exist (e.g. non-consentual images of real people, pornography, gore, misinformation, etc.). But I can imagine in a better world where we have strict regulations around image generators where art studios are granted an limited exception.

2. Let users rely on their skills

To center working artists as users, the interfaces to AI art programs should allow users to leverage their existing technical skills in new ways, rather than learning to create within the medium of text prompts or code. Interfaces like drawing tablets and MIDI keyboards have been extremely effective in this regard as expressive interfaces for other digital artforms. There is also already a variety of research on sketch-based image generation and more recently, pen-based visual prompts. I think artist centered AI art lives more in this direction, and less in text-to-image models.

Another aspect of this principle is that users shouldn’t have to code to control these systems. While programming can be part of artistic practice, it shouldn’t be required. It is totally possible to build usable interfaces for both training and generating from AI systems.

3. AI art shouldn’t replace anything or anyone

One key issue with AI art, from artists’ perspectives, is that companies are using it as a cheap replacement for human-made commercial art. An artist-centered AI image generator should not be able to generate commercial-grade images without specifying exactly what images should be produced.

Current prompt-based image generators are able to serve this role today, but it’s likely that the look and feel of AI-generated images will soon be seen as cheap and disposible. If anything (and maybe this is a topic for another post), it reveals exactly how much of current non-AI commercial art is already very similar to AI-generated images. The future is uncertain, but I’d bet commercial clients who do not want this association will still be willing to pay for images made by humans in the future.

The point of forcing users to better specify what image should be produced is not to create busy work, or artificially preserve the jobs of commercial artists. Instead, it is about requiring the user to make artistic choices, instead of leaving those choices to the generative model. Traditional artistic media require artists to decide what they want to create, and exactly how to depict it through a series of micro-decisions. Those decisions are often unconscious, but are not random, and allow the artist’s voice to come through in a work, and allow their style to naturally shift over time. AI art models today do not require the user to make those choices – they will produce an image no matter what input they are given. When details are left unspecified, the model will take a guess informed by patterns learned from its training data, leading to the emergence of a “default” style (to read more about this idea, I recommend Eryk Salvaggio’s writing on Gaussian pop).

One thing I’ve thought a lot about is whether the series of micro-decisions a person makes while drawing or painting is comparable at all to the curatorial decisions that users of AI image generators make when reviewing outputs. I don’t think that they are comparable. The reason is that those micro-decisions offer a lot of flexibility which curatorial decisions lack. A painter is only limited by the colors their paints can produce, the brushes, knives and other tools they have on hand to deposit the paints and their own fine motor skills. A curator can only select from the space of images that are produced, which occupy a much smaller portion of the space of all images. In order to increase the likelihood of high quality outputs, generative models have to reduce the likelihood of unusual outputs, but those unusual outputs are where the most novelty exists.

Conclusion

When I gave this talk, I got a positive response from the AI researchers, neuroscientists and artists involved. That said, it’s obviously easier to say how image generators should work and much harder to actually build that kind of system. If you work at the kind of place that is interested in building such a system and want to talk about design, let me know!